BOGART, Ga. -- Jay Lasley spent a year listening to Kumar Rocker pitch in high school.

It wasn’t just the sight of the 6-foot-4, 255-pound senior throwing 98-mph thunderbolts that captivated his coach. It was the sound.

Lasley would stand in the North Oconee High dugout and hear “snapping” or “flicking” noises as baseballs catapulted from Rocker's powerful right arm. In his 21 years of coaching, a baseball had never been audible to Lasley’s ears unless it made contact with a glove, bat, body part or inanimate object.

Rocker’s pitches were different. They had their own soundtrack.

“You could hear the ball come out of his fingers,” Lasley said. “It was something you just don’t hear with high school kids. The ball was snapping out of his hand when he threw his fastball.”

Lasley was sitting at a large table in a conference room Tuesday morning telling stories about the presumptive No. 1 overall pick in next summer’s Major League Baseball draft — the prized prospect who will be available to the Pirates if they want him. The coach was joined by Rocker’s former catcher, Will Cain, and his old pitching coach, Tom Dimitroff.

Tales of snapping baseballs need more than one source lest they be dismissed as urban, or in this case, rural legend on the outskirts of Athens, Ga.

And, so we went around the horn.

“Rock’s pitches had a different sound,” Dimitroff said.

“He would throw eight warmup pitches and you could hear it when he let loose and threw those first two pitches,” Cain said.

Pressed for a logical explanation, nobody in the room could provide a clear-cut answer, and 'Bill Nye the Science Guy' isn’t on staff at North Oconee. The best Lasley and Dimitroff could offer is the sound came from the pressure and grip Rocker applied to raised-seam balls used in Georgia high school baseball.

“You’re not going to get that sound with a flat-seam ball,” Lasley said. “The ones they use in pro ball are like cueballs.”

Some fans across the country first became aware of Rocker on June 8, 2019, when he fanned 19 batters and hurled a no-hitter as a freshman for Vanderbilt University in the NCAA Super Regional against Duke. It was a seminal performance that launched a thousand #TankForKumar hashtags in Pittsburgh and other big-league cities searching for a pitching savior.

Around the North Oconee baseball program, June 8, 2019, is better known as “The Day The World Met Kumar.”

“Buddies of mine from Nashville were texting me and saying, ‘This guy is unbelievable,’ ” Lasley said. “I was like, ‘Yeah, you’re welcome.’ We were lucky enough to see it for a few years.”

It’s here in the heart of SEC football country where a talented multi-sport athlete grew into a pitching prodigy.

It’s here where a community embraced an outsider and the outsider met other ballplayers who shared his vision and drive.

It’s here where his parents, coaches and teachers worked from the same playbook to help create the team-first player they say he’s become.

Vanderbilt’s rich history of player development deserves ample credit for enhancing Rocker’s rise up the draft board. But his teenage years spent in northern Georgia were the ones that set in motion his big-league aspirations.

“It was our responsibility to take care of Rock,” Lasley said. “Our big thing was we’re going to get this kid across this stage and out of this program healthy. You could just see what was coming down the line.”

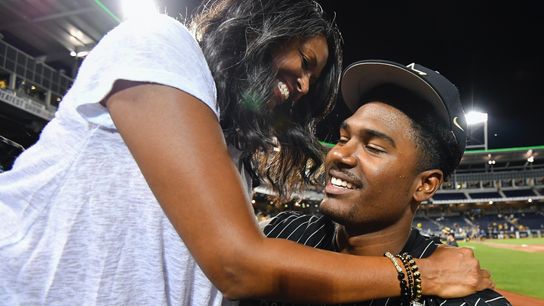

GETTY

Kumar Rocker with his mom, Lu, last year in the NCAA playoffs.

LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION

The North Oconee campus sits among acres of farmland and housing developments. It’s located off Hogs Mountain Road, the same street as rival Oconee County High in nearby Watkinsville. The schools’ football teams compete for the coveted Hog Mountain Bowl trophy. But don’t let the pastoral setting fool you. It’s a growing region that’s populated by many University of Georgia faculty and Atlanta businessmen who don’t mind the 75-minute commute to put some wide-open space between themselves and their neighbors.

In 2004, North Oconee High was built to ease the congestion of students at Oconee County. North Oconee enjoys an excellent academic reputation — it’s the top-rated school in the Athens metro area and No. 23 in Georgia, according to the annual Best High Schools U.S. News rankings. When Lalitha (Lu) and Tracy Rocker were looking for the best educational opportunity for their only child, North Oconee came highly recommended.

Tracy was a decorated football star at Auburn and played two seasons in the NFL as a defensive lineman for Washington. With Lu, the classroom always came first, and any success in sports needed an educational component.

“We had a meeting one day during Kumar’s sophomore year and it was becoming obvious he was going to be a good baseball player,” North Oconee principal Philip Brown said. “We were talking about Spanish class, and Lu looks at Kumar and says, ‘You know, you’re probably going to need to know Spanish some day.’ She was always looking ahead.”

Tracy has spent the past 28 years working as an assistant coach in the major-college and NFL ranks. It makes for a nomadic existence as assistants are often at the mercy of their head coach’s win-loss records. In 2014, the family moved to Georgia from Tennessee in time for Rocker’s freshman year.

“He was like the biggest kid in the school in ninth grade,” Cain said. “You couldn’t miss him in the halls.”

Given his size and pedigree, Rocker quickly became a starting defensive lineman on the varsity football team. It was on the baseball diamond, however, where he truly excelled.

Rocker might have evolved as a top-flight pitcher even if Tracy had accepted a job at Pitt or Ohio State. But relocating to Georgia allowed him to play ball almost year-round and put him in close proximity to an outstanding summer-league travel program. Team Elite has seen more than 150 alums drafted into the big leagues, including the Pirates’ second baseman, Adam Frazier.

The coaches at Team Elite and North Oconee worked together to formulate a plan for Rocker. It included keeping him on pitch counts so they didn’t overwhelm his golden right arm. For instance, Rocker never threw more than 30 pitches during high school games in February, starting in his junior season. Even in late spring, Dimitroff replaced him as his pitch count approached 90.

“We knew what kind of future Rock had, and we wanted him in top form for showcases in the summer,” Dimitroff said.

Rocker’s fastball clocked 82 mph as a freshman when he served as North Oconee’s No. 2 starter. His velocity jumped dramatically the following year as radar guns tracked him at 89-90 mph.

Lasley understands the importance of sharing athletes in a mid-sized high school athletic program. But the coaches and the Rocker family knew what sport gave him the best chance for college and pro success.

“I did consider football,” Rocker said. “I played into my sophomore year and I really enjoyed it, of course, but my family, they weren't going to push me to a certain sport. So I chose baseball and hopefully it works out for me.”

Baseball coaches jokingly called Rocker a “pile jumper,” in football, always the last guy to join a gang tackle. They also saw the business decisions he made when squaring up on ball-carriers.

“He always led with his left shoulder,” Dimitroff said. “He knew what he was doing.”

With his fall schedule free from football, Team Elite owner/GM Brad Bouras watched Rocker’s progress accelerate. It wasn’t just pitching, either. He worked diligently on his fielding at first base and made rapid improvement in hitting. As an underclassmen, Lasley labeled him a “6-foot-4, 255-pound Ichiro (Suzuki),” who slapped at pitches and tried to leg out infield singles. Once Rocker leveled his swing, he began driving balls into the gaps and over fences.

“He still holds our team bat-speed record,” Lasley said. “With a wooden bat, he had like a 106-mph exit velocity.”

‘MOMENT IN THE SUN’

As Rocker’s senior year began, North Oconee coaches couldn’t walk the perimeter of their stadium without bumping into major-league scouts. The pitcher had become a top prep prospect, and while it was an open secret he planned to honor his commitment to Vanderbilt, it didn’t stop talent evaluators from flocking to games.

Generally speaking, baseball players can be drafted twice: Once after their senior year in high school and, if they don’t go pro, again starting after their junior season at four-year colleges.

Demand was so high that Lasley routinely emailed MLB franchises to notify them of Rocker’s next scheduled starts. Scouts, cross-checkers and assistant general managers were spotted in the stands.

“We would get out of school at 3:30 p.m. and head down to the field around 4 for a 6 o’clock start,” Cain recalled. “And the scouts would already be there watching every move Rock made."

Such exposure can inflate the egos of some athletes, but the North Oconee staff ace refused to get drawn into the hype. In the fall, Lasley met with Rocker and asked him how the coaching staff could help ease the pressure from all the attention and expectations.

As with the sound of Rocker’s fastball, Lasley could not believe what he was hearing.

“Growing up around sports and his dad’s line of work, he embraced the team concept,” the coach said. “He got it. He understood we were working toward something. That’s not always the case in high school athletics when a kid is super talented. He told me, ‘Coach, I need this year to be about everybody.’ He knew it was a big year for him, but he knew it was a big year for others as well. With a lot of kids, their senior year is their moment in the sun. With Rock, it was like, ‘We have to spread this light around as far as it can go.’”

As a junior, Rocker benefited from the arrival of another transfer student. Chase Brice would graduate from North Oconee to become a backup quarterback at Clemson before moving on to start at Duke. Brice, who also played shortstop, formed an immediate bond with Rocker and, according to Cain, they shared similar views on leadership.

The baseball team was filled with underclassmen during Rocker’s senior season, and Cain remembers how important it was to the star pitcher that upperclassmen set a good example and communicated expectations.

Midway through the campaign, Rocker suffered a hamstring injury. Lasley planned to idle him for several weeks. He did not want to jeopardize Rocker’s long-term health or compromise his draft status. Rocker wouldn’t hear of it. While he missed his next two starts, he continued to serve as a designated hitter in hopes of helping the team win. (In Georgia prep baseball, coaches can reinsert a player twice in the same game.)

By then, Rocker and his coaches had forged a strong relationship.

“Rock came from a football background, but he has a great understanding what coaching should look like and he can identify BS from what is true,” Dimitroff said. “We were completely honest with what we thought of him. One thing we like to do is give our kids the freedom to voice their opinion and to ask questions. . . . He always brought relative questions which helped build that trust among all of us.”

The coaching staff taught Rocker to speed up his approach to pitching. His outings used to last longer than Red Sox-Yankees games. Fans could watch grass grow between pitches as Rocker circled the mound deciding on what to throw next. But by the end of his senior season, he was pitching with such pace that umpires routinely called time to allow hitters to settle back into the batter’s box.

His prep coaches dissuaded him from throwing changeups because, with a fastball approaching 100 mph, the off-speed pitch was the only chance for some overmatched opponents to make contact. Among Rocker’s biggest adjustments was his arm angle when throwing sliders. Coaches had challenged him to throw it from his highest release point. It wasn’t until after his junior season, however, when he played with an age-group national team that Rocker felt comfortable with the delivery.

“He spent part of that summer around other elite pitchers and he got more aggressive,” Dimitroff said. “Sometimes, a kid needs to see how others do it and not just hear it from coaches. He used to loop (that pitch) and roll it into the strike zone. It was like, ‘I’m going to show you this and then come back with the fastball.’ That year, he leaned to throw his slider for strikeouts. He started throwing it with the same force as his fastball, and it would tumble out of the strike zone.”

Realizing how committed he was to Vanderbilt and the price it would take to change his mind, major-league teams backed away from Rocker in the early rounds. The Rockies selected him in the 38th round of the 2018 draft.

The Rockers’ response: We’ll see you in the Vanderbilt gift shop.

“Mrs. Lu’s thing was, if he would have gone through the draft, Rock would have spent his first three years in rookie ball working his way up,” Lasley recalled. “‘If my child has a chance to be at Vanderbilt as opposed to riding a bus in rookie ball, I want my child at Vanderbilt getting a good education,’ she told me. Who could argue with that?”

GETTY

Kumar Rocker pitching for Vanderbilt.

‘MILLION-DOLLAR SMILE’

Dimitroff sat at the conference room table for more than an hour reciting his catalog of Rocker memories from high school. But his favorite story involving his former pitcher is set at Vanderbilt.

And, no, it’s not from the night of the no-hitter.

Last year, one of Dimitroff’s old mentors took a team to Nashville for a baseball clinic. After it ended, players were given a tour of the athletic facilities and the locker room. The group walked over to Rocker’s locker, and some kids began mimicking the pitcher’s windup.

“It was like when we were younger and everyone was doing Ken Griffey Jr.’s swing,” Dimitroff said.

As kids huddled around the locker, Rocker walked into the room. Jaws dropped like one of his 90-mph sliders.

Rocker spent the next 30 minutes signing autographs and answering questions.

“That’s Kumar right there,” Dimitroff said. “He was never above anybody. When he was here as a senior, he was the one coaching up freshmen. Anything he could do to help.”

Vanderbilt coach Tim Corbin tells similar stories. Rocker might have led the Commodores to a national title as a freshman, Corbin said, but he’s always learning, always allowing others to bathe in his reflective light.

Rocker said he’s comfortable throwing four pitches (fastball, slider, cutter, changeup) any time in a count.

“Right now, it’s a matter of sequencing,” he said. “(It’s a matter of) setting up batters with each pitch I throw. Each pitch having a meaning.”

It’s enough to make any Pirates fan excited about the future, assuming the organization drafts him first overall.

Some day, there will be a display case in the halls of North Oconee High paying tribute to the pitcher’s four memorable years here. Asked to name the school’s most famous alum, Principal Brown doesn’t hesitate: “It’s Kumar Rocker.”

The family has moved away from the region as Tracy now coaches at the University of South Carolina, but it remains popular with members of the school's faculty and staff.

On the night of his Vanderbilt no-hitter, Lasley, Dimitroff and Cain texted each other as the strikeout total rose and immortality beckoned. Lasley found himself screaming at his bedroom television with every punch out. It was “The Day The World Met Kumar” and everybody in small-town Bogart, Ga. (population: 1,109) was bursting at their raised seams.

As Lasley finished his interview Tuesday, the coach pulled out his cellphone and showed a picture to an out-of-town reporter. It was a photo of Rocker with Lasley’s three young daughters and two other children taken a few years ago on the field after a game.

It’s hard to tell who’s enjoying the moment more.

“He’s got that Magic Johnson million-dollar smile,” Lasley said. “I can tell you everything you want to know about Rock as a player, but I’m telling you, he’s even a better person. We’re all fortunate to have gotten to know him for a few years.”