COLUMBUS, Ohio — The phone call delivering her father’s shot at football immortality arrived on the same afternoon Hospice caregivers were making her mother’s final hours as painless as possible.

How long Lynell Nunn had waited to hear the news from Pro Football Hall of Fame president David Baker on Aug. 25, 2020. Her dad, the late Bill Nunn Jr., a trailblazing scout and key figure in building the dynastic Steelers of the 1970s, had been selected as a finalist for induction in the HOF’s contributors category.

The Nunns were gathered in the Pittsburgh home of family matriarch, Frances Mae Nunn, 93, who had never fully recovered from surgery to remove a brain tumor earlier in the summer. Lynell, her son, Matthew, and nieces, Jennifer and Cydney, were huddled near Frances’ bedside when Baker rang with word of the committee’s decision.

Lynell stepped outside the room to take the call. Her voice quivered as Baker relayed the information.

“Oh my goodness, that is such good news,” she said into the phone. “You don’t know what this means to us.”

The family won’t know for certain whether Nunn is enshrined in Canton until Feb. 6. He needs 80 percent of the HOF selectors to have voted for him — the ballots were cast on Tuesday — but the contributor committee finalist almost alway wins approval, and Nunn’s candidacy has been gaining traction for several years.

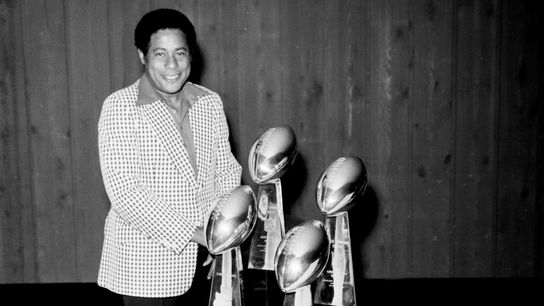

So much about the life’s work of Nunn, who died in 2014 at age 89, had involved waiting. As the longtime sports editor of the Pittsburgh Courier, he spent decades painstakingly choosing All-Star teams from Historically Black Colleges and Universities, wondering when the NFL would begin drafting players from these schools. Given the opportunity to work for his hometown Steelers in 1967, his scouting led them to select such stalwarts as L.C. Greenwood, Mel Blount, John Stallworth and Donnie Shell.

Nunn not only opened doors for Black players from small schools, but created chances for other minority scouts and members of NFL personnel departments. Although never a day passed when the Steelers and the Rooney family didn’t appreciate Nunn’s acumen, football fans outside of Pittsburgh were mostly unaware of his legacy and role in four Super Bowl titles.

“A lot of people don’t know the entire story,” said Hall of Fame coach Tony Dungy, who played for the Steelers and learned to evaluate talent at the knee of Nunn. “They don’t know what scouting was like back then and how overlooked the all-Black schools were at the time.”

WATCH: Lynell Nunn, the daughter of Bill Nunn, first learns the news that her father has been selected as the Contributor Finalist for the Class of 2021.#PFHOF21 | @steelers pic.twitter.com/NGufDjrOc6

— Pro Football Hall of Fame (@ProFootballHOF) August 26, 2020

“If the NFL was going to have the best players, they needed someone like Bill Nunn to go into the HBCUs and bring them to the attention of the National Football League,” added Hall of Fame tight end Ozzie Newsome, who became the league’s first Black general manager with the Ravens in 2002. “Bill was so instrumental in making it happen.”

In the late hours of Aug. 25, Lynell and family weren’t worried about reciting testimonials as they sat with Frances, their emotions careening between joy and grief. They just wanted to find a way to make sure she knew her humble husband of 64 years had finally earned the recognition he deserved.

“We told her alright,” Lynell said. “I don’t know how much she understood, but we whooped and hollered and told her all about it.”

'PERFECT MARRIAGE'

Five decades later, John Wooten is still salty about one of the NFL’s most legendary scouting capers.

Wooten is 84-years-old. He won a league title with the Browns as a guard in 1964, made two Pro Bowls, worked in the front office of three NFL teams, and remains a tireless champion for minority hires as chairman of the Fritz Pollard Alliance.

Despite all the accolades, the old Texan still gets agitated telling a story about Nunn, a man he adored, and believes should have been in the Hall years ago.

It was 1974 and NFL scouts were trying to get a read on an Alabama A&M wide receiver. It was Stallworth.

Some fans know Stallworth ran a disappointing 40-yard dash time and that the cagey Nunn had stuck around for another day to see him run it again on a better surface. That’s not what gets Wooten wound tighter than a banjo string, however.

Nunn had cultivated a great relationship with the coach of Alabama A&M and other HBCU schools through years of selecting All-Star teams for the Courier, one of the nation’s most prominent black newspapers.

Nunn convinced Stallworth’s college coach to give him the team’s game films. He apparently promised to make copies and share them with other NFL clubs. Nunn did no such thing. He took them to Pittsburgh and showed them to coach Chuck Noll, who was so impressed with Stallworth that he wanted to select him ahead of receiver Lynn Swann.

“Oh, the tricks of the scouting trade,” Dungy said laughing.

Wooten, working for the Cowboys at the time, found no humor in Nunn’s ingenious ploy.

Nowadays, the highlights of every pro prospect are a mouse click away. ESPN and NFL Network bombard fans with clips. The internet teems with draft evaluations.

But in 1974, there was scant information on small-school players. Scouts relied on game films, and the ones featuring Stallworth were locked away in Pittsburgh in the weeks leading up to the draft.

“I had seen John at a few practices, but we didn’t go to (HBCU) games back then,” said Wooten, his raspy voice growing more animated with each sentence. “How am I supposed to tell Tom Landry we should draft John Stallworth without him ever seeing his game films?”

The coup set the stage for the greatest draft in NFL history. The Steelers chose Swann (USC) in the first round, linebacker Jack Lambert (Kent State) in the second round, Stallworth in the fourth round and center Mike Webster (Wisconsin) in the fifth round. Nunn also advised the team to sign Shell (South Carolina State) as an undrafted free agent.

Five players. Five future Hall of Famers. Five integral members of four Super Bowl champions.

“Bill Nunn’s influence was a major factor,” said sports writer Vito Stellino, who covered the Steelers for the Post-Gazette from 1974-81. “They don’t win those Super Bowls without him — there’s no doubt in my mind about that.”

Prior to 1968, the rival American Football League had the only scouts willing to risk draft picks on HBCU schools. The Steelers’ success in mining talent from small schools put the rest of the NFL hot on the trail.

Dungy and others are quick to note that Nunn also scouted larger programs. Nunn had traveled to the University of Minnesota, where he found Dungy and talked the Steelers into not only signing him as an undrafted free agent in 1977, but converting him from college quarterback to pro defensive back. Dungy led the Steelers in interceptions a year later en route to their third Super Bowl trophy.

Nunn’s eye for talent was made more remarkable by the fact he never played football. He was an excellent basketball player at West Virginia State, another HBCU institution.

“Bill and Coach Noll were a perfect marriage,” Dungy said. “Bill would always tell Chuck, ‘I don’t know football, but I know athletes.’ Chuck’s response was, ‘I want you to bring me athletes. I want you to bring me guys with character, guys who are highly motivated people.’ That’s what Bill did for so many years.”

While scouting was his speciality, Nunn’s influence with the Steelers ran deep. He was the team’s training-camp coordinator and a vital liaison between the front office and locker room.

“Nunn developed a positive culture with the Steelers back then,” said Jim Trotter, an NFL Network reporter and HOF selector. “You are bringing in the talent from the HBCUs, many of whom have never played for a white coach. How are they going to respond? Will they trust the organization? Bill was the conduit.”

Trotter interviewed members of the Steelers and other NFL organizations to educate him on Nunn’s HOF candidacy. What he found was a pioneer who helped other minorities gain a foothold in scouting.

“There was an awful lot of pressure on Bill and guys like Lloyd Wells (of the Chiefs) because if they did not succeed, that door was probably going to close for quite some time for minorities in scouting,” Trotter said.

THE 'STORYTELLER'

Doug Whaley could not believe his good fortune. He moved to Pittsburgh at age 13, became a Steelers fan and landed a dream job with the club in the early 2000s. He also shared an office with the franchise’s resident oracle.

“I would spend hours listening to Bill Nunn tell stories about talent evaluation,” said Whaley, who joined the Bills in 2010 and served as their general manager from 2013-17. “It was better than turning on the History Channel at night.”

Whaley came to learn of Nunn’s frustrations with the league for not doing more to draft players from HBCU schools and how, in 1967, Art Rooney Sr. and Dan Rooney added him to the Steelers’ scouting staff on a part-time basis. Within two years, Nunn earned full-time employment, working his way into the front office.

Because so little was known about small-school players in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Nunn had to make compelling arguments on why the club should invest draft picks in the likes of Greenwood (Arkansas-Pine Bluff), Blount (Southern), Frank Lewis (Grambling), Ernie Holmes (Texas Southern) and Glen Edwards (Florida A&M).

“Bill told me the essence of being a good scout is being able to paint a picture in as few words as possible to people who have never seen that player,” Whaley said. “It goes back to his newspaper days. Bill was a storyteller, who also happened to be a great evaluator because of his connections in the HBCUs.”

Nunn officially retired in 1987, but remained with the Steelers through 2014, watching film, making the occasional road trip to scout and serving as a trusted advisor. He suffered a stroke in the Steelers’ offices while prepping for the 2014 draft and died a few weeks later. (The franchise renamed its draft war room after Nunn.)

His scouting success and front-office savvy would have made him an ideal general manager, but the league was unwilling to offer those jobs to minorities until the last decade.

“He would have been a great GM,” Whaley said. “There were years when he would have been the hot candidate like Nick Caserio was this year with the Texans.”

Dungy and Wooten agree rival organizations would have had a difficult time wooing him from his hometown.

“There’s no one who loved and respected Bill Nunn more than the Rooneys,” said Wooten, who lobbied the franchise to hire Mike Tomlin in 2007. “I don’t think Bill would have ever left there because he felt so appreciated in his role with the Steelers.”

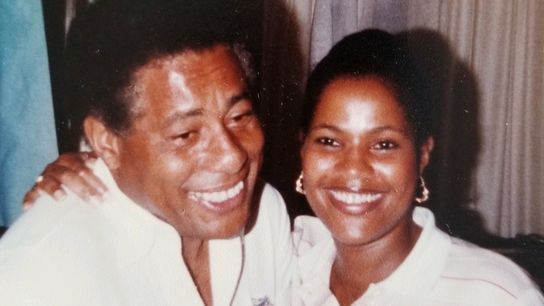

NUNN FAMILY

Bill Nunn Jr. and his daughter, Lynell.

TOGETHER AGAIN

Within hours of the HOF announcement on Aug. 25, the Nunn family went from a state of celebration to mourning. Frances died later that night.

Her loved ones like to believe she passed away secure in the knowledge that her husband was on the verge of receiving pro football’s highest honor.

“We always knew all of his accomplishments,” Lynell said. “He never made a fuss about them, but we were always tooting his horn.”

Ironically, Nunn died in the same year the Hall of Fame added a contributors category as a way to reward individuals who did not play or coach the game.

Trotter recalls his name surfacing as a candidate in 2014, but that Nunn had to wait his turn as higher-ranking executives such as Bill Polian, Ron Wolf, Jerry Jones and Bobby Beathard were enshrined ahead of him.

“Teams were not hiring Blacks to run their football operations,” Trotter said. “We can’t judge Bill Nunn and Lloyd Wells or others on the same standard as we do a Bill Polian or Bobby Beathard or Ron Wolf. We have to judge them on the job they were given and how well they did it.

“Bill Nunn stood out in that job. Over time, fellow committee members started to consider that context, and that’s where his name and candidacy gained momentum.”

USA Today sports writer and HOF selector Jarrett Bell said Nunn’s nomination as a finalist is “long overdue.”

“I know you can say that about a lot of people,” Bell explained. “But Bill Nunn was a pioneer in the scouting world. He gave players opportunities in the league that were not available before him.”

Dungy, who serves as an at-large HOF selector, thinks often of the lessons Nunn taught him. The former coach won a Super Bowl with the Colts in 2006. Two youngsters making contributions to that club were small-school safety Antoine Bethea (Howard) and defensive end Robert Mathis (Alabama A&M).

"It was almost inconceivable to most of the NFL world that John Stallworth could possibly be as good as Lynn Swann," Dungy said. "That was the beauty of Bill. He could look at guys who didn’t have all the benefits, and project what they could be. He could then get that across to other people. He could see L.C. Greenwood as a rail-thin, undersized defensive lineman developing into a good player with two or three years with us and an excellent weight program. He could project that, and I learned that from him."

The Hall of Fame might need to hold two ceremonies this summer in Canton — one for the Steelers, another for the rest of the league.

Former guard Alan Faneca is also among the finalists. If elected, they would join Class of 2020 members Troy Polamalu, Bill Cowher and Shell, whose enshrinements were delayed because of the coronavirus pandemic.

Nunn’s potential induction comes one year too late for Frances, who like so many members of her family was educated at an HBCU.

The Nunns are filled with high achievers. Lynell is a former federal prosecutor. Her late brother, William Nunn III, was an actor who appeared in multiple movies, playing Radio Raheem in “Do The Right Thing” and Robbie Robertson in the “Spider-Man” trilogy.

As Nunn’s long wait for national recognition comes to an end, Lynell finds solace in the incredible timing of the call from the Hall last summer.

“We like to think mom and dad wanted to celebrate together that night,” she said.