COLUMBUS, Ohio — Cam Heyward arrived at Heinz Field on Sunday wearing a No. 34 Pitt jersey to honor his late father on what would have been his 55th birthday.

From the time he was a boy growing up in Monroeville, the Steelers’ All-Pro defensive lineman heard all the Bunyan-esque tales of Craig 'Ironhead' Heyward’s time with the Panthers in the mid-1980s. With his SpongeBob physique, he could punish defenders with his size and surprise them with his agility.

There are so many great stories about the prodigious character who was a Heisman Trophy finalist in 1987 and a bruising NFL running back for 11 seasons. But his oldest son volunteers another Ironhead story that few know. It’s one that illustrates a different kind of strength, one that illuminates a family legacy that Cam Heyward carries on today in Pittsburgh.

In the winter of 2005, his cancer-stricken father had been confined to a wheelchair. The disease had taken a massive toll on his body, but had done nothing to tame his streak of stubbornness. Ironhead began a physical therapy regimen with the goal of walking across a high school football field in Georgia.

“He was determined to accompany me out on the field for my Senior Night,” Heyward recalled.

A stroke ended that dream in February of 2006. Three months later, Ironhead died of complications to brain cancer at age 39. For all of the devastating blocks and bone-rattling runs, it was those last few yards that he could not gain that left a lasting impression on his son.

“The thing I admired about him more than being a football player was that he wanted to be my father,” Heyward said. “He wanted to be there for me, and he wasn’t going to let an illness stop him.”

The Heyward legacy will add another chapter in the coming weeks.

Although there’s been no official confirmation, Charlotte Heyward, mother of Cam and ex-wife of Ironhead, said the university plans to honor members of Pitt’s athletic hall of fame classes of 2020 and 2021 in a ceremony most likely tied to the Oct. 23 football game against Clemson. Ironhead was named to last year’s class, but the global pandemic forced the school to postpone the induction.

While there’s no shortage of talented father-and-son athletic duos, rarely have their glories been linked to the same professional and collegiate city. Heyward is proud of evolving into one of the NFL’s best defensive linemen in Pittsburgh, his hometown and the place that gave rise to the legend of Ironhead.

“Being from Pittsburgh, it was always special to my heart,” he said. “The sense of appreciation only grew as I got to hear stories about my dad and realized how rare it was to play in the same city. Being drafted by the Steelers, it was a dream come true.”

____________________

CAM HEYWARD

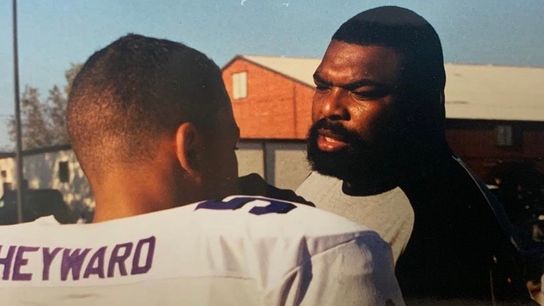

Cam Heyward with his father, Craig 'Ironhead' Heyward during Cam's high school career.

Only Ironhead Heyward could make a Loofah seem manly. His larger-than-life persona was such that Proctor & Gamble cast the burly running back as an unlikely pitchman for Zest soap during his NFL playing days.

He filmed several commercials lathering his 5-foot-11 frame — one that could fluctuate between 250 and 320 pounds during the offseason — with a spongy, handheld scrubber that he referred to as a “Thingy.” Who else but Ironhead could bury blitzing linebackers on the field and exfoliate dead skin cells in the shower?

The carefree football player had an appetite for life and he wasn’t shy about going back for second and third helpings.

“I really wish my (three) kids could have experienced my dad and seen his personality,” Heyward said. “That’s one great thing about YouTube. They have gotten to see some of his highlights. I want them to see those Zest commercials, too.”

Cam and Ironhead share a similar How-I-Met-Your-Mother backstory. Charlotte and Ironhead fell in love as students at Pitt. Cam and his wife, Allie, did the same at Ohio State.

Charlotte grew up in Pittsburgh and her family adored the Steelers. Her mother, Judy, a former school teacher, still lives in the Highland Park home where Charlotte was raised.

Life with Ironhead was never dull.

“There was always something going on with him,” Charlotte recalled. “He just had that way of making me laugh.”

A native of Passaic, N.J., Ironhead could stress opposing defenses and his own coaching staff alike. He arrived in Pittsburgh with a nickname given to him by his grandmother. He was known for lowering his massive skull into the midsections of would-be tacklers in street football. He also barely flinched the day a boy broke a pool cue over his head at a Boys & Girls Club in Passaic.

Longtime Pittsburgh sportscaster Bill Hillgrove remembers the Pitt equipment staff having to special order his helmet to accommodate his 8-3/4-inch hat size.

“I joked that the helmet was delayed in getting here because it was delivered by a Dravo barge, which carried steel up and down the Ohio River,” Hillgrove said.

Ironhead rushed for 1,791 yards in his final season at Pitt and was among five finalists for the 1987 Heisman Trophy awarded to Tim Brown. Hillgrove and a camera crew went to New York for the ceremony and Ironhead squired them around Passaic on a side trip, showing them some of his favorite haunts.

“He took us to this hot dog shop,” Hillgrove recalled. “He ordered this hot dog that had everything on it. I mean this thing had mushrooms and French fries, and he was just devouring it with this big smile on his face. That was Ironhead. He always had that smile.”

Hillgrove feels fortunate having broadcast games featuring two generations of Heywards. When the Steelers drafted Cam in 2011, the sportscaster marveled at the facial resemblance of father and son.

Charlotte said her oldest of four kids and her ex-husband shared other characteristics — stubbornness, competitiveness, tenacity and a love of dry humor. They also appreciated the need to help the less fortunate. The family made its offseason home in Pittsburgh when Ironhead played in the NFL, and he rarely passed on an opportunity to visit kids at Children’s Hospital.

“Everyone always had unique stories about my dad and you could tell by the way they told them how much they enjoyed being around him,” Heyward said.

____________________

Ironhead Heyward rushed for 4,301 yards and earned one trip to the Pro Bowl during his NFL career from 1988-98. His numbers and honors might have been greater had he exhibited more self-control off the field. He partied the way he played — attacking everything head on, full go. His weight problems, alcohol issues and several scrapes with the law contributed to him playing for five teams over 11 seasons.

“I was an idiot,” Ironhead once told Sports Illustrated. “I was all about getting drunk. Man, we'd go out there and drink a case of beer and a couple of bottles of tequila. We'd be out there wilding. Then, at the end of the night, I'd go to one of those all-night places and have four or five of those big Polish sausage sandwiches.

"Get home at 4 or 5 in the morning and still have to be at practice at 8 a.m. I'd be at practice still drunk. I didn't care. I wanted to be the big man. . . . For a lot of years, I made my bed hard, and it was tough to sleep in it.”

The Bears sent Ironhead to rehab for 30 days in 1994 as a condition for returning to the team. Heeding the counselors advice, he remained in the program for an additional 60 days. The Bears ended up releasing him, but the rehab stint proved to be a turning point. Ironhead never drank again, Charlotte said.

“It’s no secret my dad struggled with alcoholism,” Heyward said. “He was very open about it. He struggled for a long time and then, from what I heard, he went cold turkey. What that taught me is it’s OK to admit weakness because really that’s a sign of strength.”

Charlotte said her boys grew up in a house that was alcohol free. She explained to them that both their father and their grandfather suffered from the same addiction, and cautioned that it could be hereditary. She believes her kids took the message to heart.

While the couple divorced in 2001, they remained “close friends” and Ironhead moved into an Atlanta home just down the street from his family.

Heyward said his father was present at most of his sporting events and school functions even as he spent the last seven years of his life battling a reoccurring brain tumor. The illness, which helped bring an end to his football career, led to bouts with depression, Charlotte said, but it couldn't stifle his fun-loving spirit. Heyward recalls his dad blasting his car stereo early in the morning as he dropped him off for school and arriving at an assembly wearing a satin gold suit. Ironhead's penchant for baiting referees was legendary, and it led to multiple ejections.

“He’s the only person I know that’s been thrown out of a church league basketball game,” Heyward said. “He was definitely passionate.”

But the Steelers’ veteran said both of his parents played vital roles in shaping his life as a man and a father. Heyward has been a model athlete wherever he’s played.

“Cameron’s eyes were always wide open,” said Jim Tressel, who coached him at Ohio State. “He had a desire to always do what was best for the team and he was motivated to do greater things. You could tell his father had given him a real head start down that path.”

____________________

PITT ATHLETICS

Craig "Ironhead" Heyward at Pitt in 1987.

Heyward grew up with the stability his father never knew as a child. He’s never taken for granted the advantages he enjoys, but he’s also never been satisfied with basking in reflected glory. He wanted to build, not rest, on his father’s legacy.

He credits Tressel for reinforcing that desire during their time together at Ohio State. Tressel is the son of a famous small-college football coach, and as he rose through the ranks he wanted to make his own mark on the game.

“Coach Tressel would say jokingly, ‘My dad had a street named after him, but I want a highway named after me,’” Heyward recalled. “My dad created a name for himself in Pittsburgh at a young age and he set the bar super high, but I wanted to attain something like that, or even greater.”

GETTY

Cam Heyward at Heinz Field.

Heyward has become one of the Steelers’ most indispensable players and leaders. The 32-year-old has reached the Pro Bowl each of the last four seasons, twice earning first-team, All Pro honors. And while the club is mired in a 1-2 start to the season, his performance remains exemplary. Pro Football Focus ranks him as the NFL’s highest-graded defensive player through three weeks.

He not only understands his place on the team, but the history of the great players donning Steelers’ uniforms before him. Last Friday, he wore a gold No. 75 jersey as a tribute to Joe Greene, who was celebrating his 75th birthday.

All love for Joe Greene 🙌@CamHeyward pic.twitter.com/AtnNiybwRW

— Pittsburgh Steelers (@steelers) September 24, 2021

“They got me wearing your jersey,” Heyward said in a video message to Greene. “I know it doesn't mean a lot to you, but it means a lot to me. You’ve always been a big mentor, a hero in the community, (and) on the field.”

Heyward’s favorite jerseys, however, are the ones bearing his father’s name — gifts given to him and his brothers from the Pitt athletic department. There are times when he’s thinking about his dad that he will reach into the closet and put one on. It doesn’t have to be a special occasion like a birthday.

His foundation, the Heyward House, is another way he honors his father. The charitable organization, which is run by Charlotte, helps serve disadvantage youth in the Pittsburgh area. It features many forms of outreach, but one of the most personal is “Craig’s Closet,” which provides high school boys with free dress clothes for interviews, internships, banquets and proms.

Ironhead could afford only one suit during his time at Pitt and he would try to disguise the fact, Charlotte said, by wearing different shirts and ties with it. Founding a program to supply kids with dress clothes was one of Ironhead’s goals before he died. His son has made his father’s vision a reality.

“I was a kid who was pretty blessed and given a lot of opportunities, but I know a lot of kids who weren’t,” Heyward said. “That’s the main thing I want to do. I want to provide opportunities and give kids chances to succeed in their lives. . . . Getting someone to feel good about themselves goes a long way in life. The only thing that sucks is my dad never got to see it happen.”

Grateful for the life he leads, Heyward still admits to feeling robbed by losing his dad at such a young age. Each milestone he reaches as a player and a parent is tinged with sadness in knowing Ironhead can’t be there to share in it. It will happen again in a few weeks when Pitt enshrines his father posthumously in its athletic hall of fame.

There’s at least one life-altering moment, however, when Heyward felt his dad’s presence. It came on the night of the 2011 NFL Draft as he tumbled down the board and into the waiting arms of his hometown team at No. 31 overall.

“I really wanted to go to Pittsburgh, but you never think it’s going to work out like that,” Heyward said. “The stars kind of aligned. My mom always says God and my dad were working this out up top so I would go to the Steelers.”

It’s enabled Heyward to carry on a family legacy — sans the gold satin suit.