MADISON, Wis. — Mark Johnson stands on a terrace overlooking LaBahn Arena and delivers a spot-on imitation of the man who made almost every day a great day for hockey in Pittsburgh 30 years ago.

You don’t need to close your eyes to envision the late Bob Johnson speaking about the benefits of oatmeal or the Penguins playoff chances in that giddy spring of 1991. The 64-year-old son, who’s upholding the dynastic hockey legacy that Badger Bob established at the University of Wisconsin, strongly resembles his father. Right down to the prominent hawk-like nose on his weathered face.

On a chilly Thursday morning, Mark talks reverently about the father who carried lofty ambitions through life while finding joy in its simplest pleasures. Badger Bob loved a good breakfast, and he spent many mornings in the hospital cafeteria across the street from the old Civic Arena.

“‘Oh it’s a great deal. For a buck, 99 ($1.99), you get two scrambled eggs, you get your toast, you get your hash browns, you get the coffee,’ ” Mark said in his old man’s voice.

The Wisconsin women’s hockey coach and former Penguins forward, who played in Pittsburgh during the early 1980s, can impersonate his father better than anyone. However, he’s hardly alone when it comes to mimicking a mentor whose passion and enthusiasm for the sport knows no equal. Invariably, everybody who shares a Badger Bob story feels compelled to emphasize its high points using his cadence and pitch. Often times, they don’t even realize they’re doing it.

It’s the most amazing involuntary act in hockey.

"‘You know, boys, the lion starts every day by stretching,’” Penguins radio analyst and two-time Stanley Cup champion Phil Bourque said recalling Badger Bob’s emphasis on flexibility. “‘You are the most powerful beasts in the jungle.’”

Gazing across the empty campus rink, Mark laughs at the memories of his dad, the quirky and innovative coach who died at age 60 of brain cancer on Nov. 26, 1991, just five months after leading the Penguins to their first Stanley Cup. Even the sight of six NCAA women’s championship banners that adorn the arena’s rafters spark stories about him.

“When he got to Pittsburgh, he kept looking up to the Civic Arena ceiling and saying, ‘We’ve got to get some banners up there, we’ve got to hang some banners.’” Mark recalled. “He had a vision of what he thought they could create, and in his mind he knew what it was going to look like.”

Thirty years later, five Stanley Cup pennants flutter above the ice at PPG Paints Arena — the site of the old hospital where Badger Bob took friends and fellow coaches to dine after morning skates.

In Pittsburgh, we mark the passage of time by the eras of great coaches. The long runs of Chuck Noll, Bill Cowher, Mike Tomlin, Danny Murtaugh and Jim Leyland. Mike Sullivan is building one of his own with two Cups already in his account.

Badger Bob gave the city only one season, but he remains as relevant today as that June night in Bloomington, Minn., in 1991 when he hoisted the Cup and proclaimed, “I’ve reached the top of the mountain.”

His favorite catchphrase, “It’s a great day for hockey,” is emblazoned on the wall above the Penguins stick rack and it still serves as the organization’s mantra.

“Badger became an icon in Pittsburgh in about a year and a half,” said Kevin Stevens, a special assignment scout for the club and a former two-time, Cup-winning forward. “How many people can do that in any city?”

____________________

PENGUINS

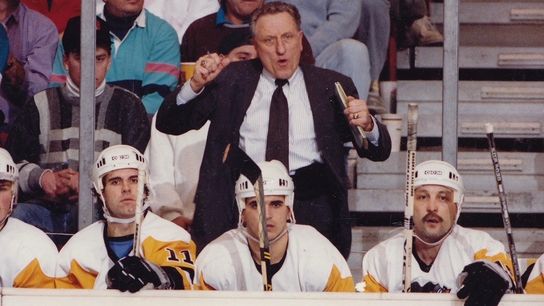

Bob Johnson behind the Penguins bench during the 1990-91 season.

Former defenseman Larry Murphy can still picture the scene: a homesick 18-year-old Jaromir Jagr struggling to adapt to life in North America and his head coach attempting to console him.

Murphy had just arrived in Pittsburgh via a midseason trade — one of many made by general manager Craig Patrick during the 1990-91 campaign. Everyone recognized the teenage winger’s awesome potential. They also saw a young man tormented by the language barrier and his adjustment to the NHL game.

The league historically has been slow to embrace change and adopt progressive measures. Tough love was rule of the day. There was no room for feelings when Bob Probert, Marty McSorley and Dave Brown were taking regular shifts.

Badger Bob saw it a different way.

“Jagr was overwhelmed that first year,” Murphy said. “I can remember seeing Badger skating over to him and putting his arm around Jags. He really brought him around at his own pace.”

A few days later, the Penguins traded for fellow Czech forward Jiri Hrdina.

“Jiri was a good player in his own right and he helped us that year,” Murphy said. “He also really helped Jags adjust. Just having a fellow countrymen on the team was a real boost.”

Nowadays, the importance of monitoring an athlete’s mental health is splashed all over the headlines. We saw it in the recent Olympics with gymnast Simone Biles. Canadiens goalie Carey Price has addressed his own issues, admitting he let himself “get to a very dark place.”

Badger Bob was light years ahead of the curve. His focus on the individual dated to his days teaching history at a Minnesota high school, where he used a hockey stick as a pointer. He grew to understand the psyches of various athletes at Colorado College, where he coached the men’s hockey team and served as an assistant in the football and baseball programs.

At Wisconsin, he learned about the pressures confronting a coach’s son. Mark was a member of the Badgers national championship team in 1977 before becoming one of the Miracle On Ice heroes that beat the Soviets three years later in Lake Placid, N.Y.

“Badger would tell a player to take a day off or go do something with his family,” recalled Penguins television analyst Bob Errey, who won a pair of Cups in Pittsburgh. “He legitimately cared about your well being, your mental health. We’re not talking 2020, we’re talking 1990. He cared about your well being and that wasn’t high on the priority list back then, if you know what I mean.”

PENGUINS

Reminders of Bob Johnson's legacy are etched on the walls inside the Penguins' locker room.

Events from 30 years ago tend to cloud memories. While the Penguins won the Patrick Division en route to capturing the Cup, the Jagr drama was only one of many issues Badger Bob needed to overcome. Mario Lemieux didn’t play a game until late January due to an infection he developed following back surgery. The Penguins were out of the playoff picture until early March when Patrick swung the legendary trade-deadline deal for Ron Francis and Ulf Samuelsson.

Former beat writer Tom McMillan, who recently retired from his post as the franchise’s vice president of communications, said Badger Bob did a masterful job of incorporating the influx of new players throughout the 1990-91 season. Patrick added that his coach’s calming influence on the ice was matched only by his steady hand in dealing with roster problems behind the scenes.

“We had a game where we lost something like 7-0,” Patrick said. “He walked into the room and took a swing with an imaginary golf club and said, ‘Back to the practice tee tomorrow, boys.’ You just didn’t see that with coaches. It was the kind of stuff that helped players really buy in.

“He came into my office only once that season. He closed the door and said, ‘Craig, we need to get a couple defensemen.’ We had a chat about it and he got up and left. Lo and behold, we were able to pick up Murphy and Ulfie later that year. That’s only time he asked me for anything.”

____________________

PENGUINS

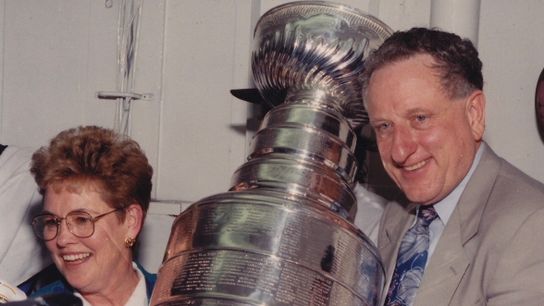

Bob Johnson and his wife, Martha, with the Stanley Cup in 1991.

The Penguins were preparing for a training-camp practice in Vail, Colo., when Bourque saw Badger Bob grab a microphone.

It’s not uncommon nowadays for NHL clubs to hold team-building sessions in cities away from the franchise's home base, but it was a fairly novel concept in 1990. The old Vail arena was filled with spectators, and Badger Bob decided to serve as the emcee.

“He’s describing the drills to the fans like he’s doing play-by-play,” Bourque recalled. “‘Next up in line for the horseshoe drill, No. 25, Kevin Stevens. He’s a big boy, folks. He’s gonna score 50 goals in this league.’ We’re standing in line asking ourselves ‘is this (expletive) real? Is this the National Hockey League? It took us a while to realize this wasn’t some ‘crazy uncle’ routine. This was real. This was who he was.”

For decades, the NHL was 20 years behind the rest of the sports world and pulling the emergency brake. California Golden Seals maverick owner Charlie Finley was mocked for allowing his team to wear white skates in the 1970s. Fox Sports was crucified for introducing “glowing pucks” to its telecasts in the 1990s.

So you can imagine the reaction when the Flames named Badger Bob, fresh from his run at Wisconsin, as their new head coach in 1982. Only once before had a coach — Ned Harkness in 1970 with the Red Wings — gone straight from the college ranks to the NHL.

Badger Bob not only made the transition, but he started populating his roster with former U.S. college players such as Joe Mullen, who played for him in Calgary and Pittsburgh. The Flames qualified for the playoffs in each of Badger Bob's seasons and reached the Cup final in 1986, losing to the Canadiens in five games.

“He’s the reason I wanted to coach,” said Mullen, a former Penguins and Flyers assistant. “He wasn’t afraid to take chances and try new stuff. What he taught you was the kind of stuff you could take home and use every day of your life.”

When Badger Bob entered the NHL in 1982 just 9.52 percent of its players were American born. The opening-night percentage this season was 27.19, the most in league history. The Penguins won their first two Cups with Boston native Tom Barrasso in nets and clinched their most recent title in 2017 with Nebraska-born Jake Guentzel leading all playoff goal scorers.

But it wasn’t just the willingness of Badger Bob to give Americans a shot at the NHL level that made him unique. He blasted through the walls that once divided coaches and players like Kool-Aid ready to serve up a blend of positivity and lightheartedness.

“He loved to talk about oatmeal,” Bourque said. “He’d come up to you in the morning and say, ‘Hey, did you get your oatmeal today?’ He held players accountable, but he got to know them as people. The season can be a grind and he found ways to make it fun.”

Patrick referenced a trip to Boston when the team bus got stuck in traffic because of roadway construction.

“Guys are jackhammering all over the place, and I hear Badger from the front of the bus say, ‘Hey, Kevin, that could be you! That could be you every day! You want to be doing that or do you want to be on the bus with us?’ ” Patrick recalled.

McMillan said Badger Bob was not universally beloved, as is often portrayed. Several of the Penguins players, who were frequently held out of the lineup, privately referred to him as “a college coach.” Over time, the group came to appreciate his process and methods.

“You are only as strong as your weakest link,” Bourque said. “He’d see a guy who was struggling, not playing well, and tell him, ‘I’m gonna need you. I’m gonna need you to score a big goal.’ And instead of being down and feeling like shit, Badger just pulled you out of the dumpster and made you feel like the best player in the league.”

Badger Bob relied on more than the power of positive thinking. He found attention-grabbing ways to get his points across such as the time in Boston, during the conference finals, when he summoned his players to a hotel ballroom, where he had the Penguins work on power-play breakouts while they were dressed in suits.

McMillan said the coach was cutting edge in his views on nutrition, stretching and breaking down opponents years before analytics and the internet made the task easier. Every practice, every drill and every unexpressed thought was documented. Badger Bob filled more notebooks than the beat writers assigned to the team.

“After the Penguins hired him, I went to Colorado to do a story on him,” McMillan said. “He showed me all the notebooks. ... He had a notebook from every Calgary practice that he coached. ‘Here’s Dec. 1. Here are the drills we did that day and here is how I graded the players.’ One time during the World Championships, he got a media credential to attend a Czech practice. He went there to diagram the Czech power play. He was so far ahead of his time in many ways.”

____________________

TOM REED / DKPS

Mark Johnson inside LaBahn Arena, where he's led Wisconsin's women's team to six NCAA titles.

Mark Johnson didn’t know what to expect when he arrived at Mercy Hospital on Aug. 30,1991. He had flown all night from Europe after receiving a phone call alerting him that his father had taken ill with stroke-like symptoms at a restaurant while dining with his wife, Martha.

Just two months after he had “reached the top of the mountain,” Badger Bob was coaching Team USA in the Canada Cup and using Pittsburgh as its home base. Although characteristically upbeat, friends noticed that his speech was slightly slurred and his coordination had become an issue when eating. The old coach thought it might be a dental problem, and he had planned to get it checked.

Instead, it was brain tumors. One was removed during emergency surgery, the other was inoperable. Badger Bob had cancer.

Mark braced himself as he walked into the hospital room, expecting to see his dad surrounded by family members and doctors. He couldn’t believe the sight that greeted him.

“There’s Chris Chelios, Gary Suter and Pat LaFontaine and a few other guys from Team USA,” Mark recalled. “My dad’s got his yellow notebook out. His right side was paralyzed so he can only write with his left hand even though he was a right-handed writer. He’s trying to diagram what these guys needed to take back to the coaching staff. He’s writing drills they need to do that day at practice. I’m like, ‘why would I expect anything else?’”

Over the next few weeks, Badger Bob prepped the Penguins coaching staff from hospitals in Pittsburgh and Colorado Springs. He stayed in constant contact with Scott Bowman, who coached the team to a second consecutive Cup win.

“Until his final breath, he was thinking about ways to improve our power play,” Bourque said.

The team saw him one last time as the Penguins played an exhibition game in Denver. He watched from an arena suite sitting upright in a hospital bed.

Patrick delayed the banner raising ceremony until November in hopes Badger Bob would be healthy enough to attend, but his condition only worsened.

On Nov. 27, 1991, a day after he died, the Penguins honored their coach with a tribute prior to the start of a game against the Devils. “It’s a great day for hockey,” was painted onto the ice. “Badger” patches were stitched onto uniforms. Battery-powered candles were held by fans and players alike as the house lights were dimmed and hymns were played.

“We’re all standing in a circle at center ice and this sad music is playing,” Bourque recalled. “I remember one or two of my teammates started to cry. That was it. Almost everybody broke down, guys just weeping moments before the start of a game. It was heart wrenching.”

The Penguins rallied to win 8-4 and Lemieux dedicated the remainder of the 1991-92 season to Badger Bob. His name was etched on the Cup again even though he died months before they raised it.

Legacies are sometimes hard to define. Badger Bob meant many things to many different people. McMillan thinks he’s remembered to this day in Pittsburgh for giving the franchise belief when little existed before his arrival.

“He created the culture of positivity and optimism that led to all the success over the years,” McMillan said. “Before he got here, the Penguins hadn’t won anything. He wanted to bring banners to Pittsburgh. . . . He created that kind of feeling around the team to the point where his pet saying, ‘It’s a great day for hockey,’ is still the one the Penguins use as their slogan.”

Back in Madison, Mark keeps his father’s notebooks tucked away in his home. He’s pulled them out over the years and found nuggets of information he can use to coach the women’s team.

Badger Bob’s image and memorabilia are festooned on the concourse walls and trophy cases inside the adjacent Kohl Center, home to the men’s hockey program. The bright red sports jacket he wore on game nights is proudly displayed.

“It was hard for everybody because he was at the pinnacle of what he wanted to do,” Mark said. “Then, you blink and you realize how precious life is. To see him deteriorate so rapidly it didn’t seem fair, but sometimes life isn’t fair. You have to make the most of every day and, as you reflect back on it, he was able to do just that.”

Mark Johnson stands silent for a moment on the terrace before retreating to the conference room. The only thing left standing watch over the arena is all those beautiful banners.