In a nation where little is agreed upon and much is debated, Cam Heyward could have launched a political campaign with just two words following the Steelers’ 16-16 stalemate against the Lions on Nov. 14 at Heinz Field.

“Ties suck,” the frustrated Steelers defensive lineman said.

Whether you’re Democrat or Republican, Beatles or Stones, “Breaking Bad” or “The Wire,” most Americans are willing to reach across the aisle and compromise on one talking point: There has to be a winner and there has to be a loser. Baseball fans sent that message with venomous clarity to former MLB commissioner Bud Selig when he declared the 2002 All-Star Game a 7-7 draw after 11 innings.

In a recent discussion with DK Pittsburgh Sports, former Pirates pitcher Mike Williams sounded like a worthy Heyward running mate in expressing his views.

“That’s why you play the game,” said Williams, who participated in the infamous Midsummer Classic sister kisser in Milwaukee. “That’s what you prepare for, that’s what you practice and scrimmage for. It’s not about being as good as someone else, it’s about being better than someone else.”

It’s a quintessential American attitude that seems to separate us from the rest of the sports-loving globe. Let the world have its ties and its metric system — we want finality to our games. And we’ll go to 15-round hockey shootouts and nine-overtime college football games (hello, Penn State and Illinois) to achieve it.

On this side of the Atlantic Ocean, the only draws that excite the masses are found in spaghetti Westerns.

“I fully understand the American hatred of ‘ties,’ as you call them,” wrote Ian Darke, an English soccer commentator, in an email response. “I think it is one reason cricket is a mystery to most Americans. They can’t understand how a ‘test,’ match can last five days and end in a draw. As you say, the culture is very different in (the United Kingdom) and Europe.”

Pittsburgh fans are nodding their heads in agreement. It’s why there was almost more satisfaction in watching their shorthanded Steelers fight to the end in a 41-37 loss to the Chargers than seeing their club tie the lowly Lions.

Unfortunately, the Steelers have more experience in this unsavory result than they care to admit. Only the Bengals have more ties (four) than the Steelers (three) in this century. Who can forget the 21-21 deadlock with the Browns in the 2018 season opener? It's the game that prompted this pearl from safety Terrell Edmunds:

“Honestly, at one point, I was like, ‘OK, I’m ready to go back out. Let’s get right. Let’s go stop ‘em.’ And they were all like, ‘It’s just a tie, bro.’ I was like, ‘Oh man.’”

A vote for Heyward is a vote to abolish the tie.

____________________

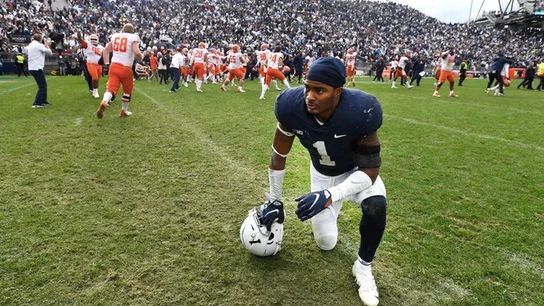

GETTY

Penn State safety Jaquan Brisker reacts as Illinois celebrates a 20-18 win in a nine-overtime game at Happy Valley.

No American sports enterprise wraps itself in the flag more than the NFL. It’s the league that loves fighter jet flyovers and swaddles its coaching staffs in camouflage sideline garb once a year. It’s also the only league among the four major sports that allows its games to end in ties.

College football distanced itself from draws in 1996. The NHL got rid of them after the 2004-05 lockout. The NBA has never tolerated them. Baseball would rather let position players soft toss a few innings than see a game end in a tie. (The Pirates did play a 1-1 rain-shortened contest against the Cubs late in the 2016 season because the outcome had no bearing on the playoff races.)

Somehow, the NFL has not followed the trend. Maybe, it’s the league’s way of trying to popularize its product in England. Hey, come see the Jaguars and Browns at London Stadium and you might see a draw.

Ten regular-season games have ended in ties since 2012, and the league’s decision to shorten the overtime period from 15 to 10 minutes in 2018 has led to at least one stalemate in each of the last four seasons.

Steelers coach Mike Tomlin, a member of the NFL’s competition committee, was asked about the topic last week after his team fumbled twice in overtime, denying it a shot at beating the winless Lions.

“We continually look at things such as that,” Tomlin said. “Those discussions are centered around player safety. We want to have sufficient enough time to determine a winner, while at the same time working to minimize the number of snaps a group could play in a game because you’ve got another game waiting on you, usually within six or seven days.”

Almost without fail, every NFL tie is accompanied by admissions from a few players who had no inkling a game could end without a winner. Steelers rookie Najee Harris volunteered his name to that list. It’s less about not knowing the rules and more about coming through the high school and college ranks, where outcomes are always settled on the field. As the Nov. 14 game at Heinz Field headed to overtime, Lions running back Godwin Igwebuike confessed that he and some of his teammates discussed the length of extra time. When he asked for clarification, Igwebuike said some players on the Lions sideline thought there could be “two” or “three” OT periods.

Count Murray State professor Daniel Wann, the preeminent authority on American sports fan behavior, among those who believe the NFL should adopt a format similar to college football.

“Truth in advertising, I think ties are terrible, but that’s how we were brought up —you play until there’s a winner,” said Wann, who’s written two books and more than 150 research papers on sports fanaticism. “Ties are not satisfying because, in our minds, the game is not over yet.”

Author Michael Weinreb, who’s written extensively on college football, said the nation’s dim view of ties illustrates our worldview.

“It feels like American football should be above that,” said Weinreb, author of “Season of Saturdays.” Maybe that’s American exceptionalism working its way into the sport. There’s something in the American blood that doesn’t want to settle for ties. That’s something those wussy Europeans do.”

His last statement was said jokingly. Because as Weinreb grows older and watches sports leagues invent contrived methods for ending stalemates, he believes some games are simply fit to be tied.

Weinreb is a Penn State graduate and a Nittany Lions fan. He was flabbergasted by the nine-OT game in Happy Valley as Penn State and Illinois began trading two-point conversion attempts to decide the outcome.

“It was like, ‘what am I watching here?’” Weinreb recalled of Penn State's 20-18 loss. “It’s like a gymnastics exhibition. This isn’t football. It was the closest thing to a hockey or a soccer shootout. It didn’t feel right. If you are going to push this mythology that football is a game for tough guys and perseverance and crap that we do in America, this isn’t the way to do it. It was just weird, and it certainly didn’t shorten the game.”

But Weinreb agrees with Wann and others in thinking that the NFL needs to explore a different overtime format.

“It feels demoralizing or demeaning,” he said. “People want a zero-sum game. They don’t want any ambiguity at all.”

____________________

GETTY

Newcastle United fans show their support in the face of relegation during the 2016 season.

You want a soccer coach who gets you, America? Move over Ted Lasso. Make way for United States men’s national coach Gregg Berhalter.

“I don’t like the tie in football,” Berhalter told DK Pittsburgh Sports on Tuesday. “That’s a little funky.”

Before adding Berhalter to the Heyward-Williams ticket, understand he doesn’t have a problem with draws in soccer.

Context is necessary to appreciate such a view. Let’s start with the obvious: Soccer is a low-scoring sport, adding to the probability of a tie after the regulation 90 minutes expire. Domestic and international tournaments, as well as the MLS playoffs, feature 30-minute overtimes. If there’s still no winner, a shootout follows.

In the regular season, games can end in ties because nobody wants to subject teams to such grueling extra time on a regular basis.

“I think really there's a sense of fairness to it,” the BBC’s James Wickham wrote in a Twitter direct message from Manchester, England. “If the two teams are well matched, why does one have to win? Isn't the sporting contest in the struggle, rather than the result?”

American fans like to think their support inside a stadium can sway outcomes. It’s a belief that’s given rise to such designations as “The 12th Man” and “The Fifth Line.” In Europe and South America, the arena experience is often more intense for visiting teams.

The playing of “Renegade” pales in comparison to threats of physical and verbal intimidation aimed at players and match officials. Hardly a month passes without stories regarding athletes being targeted with racial taunts from fans. It all plays into the mindset of visiting teams.

“The hostility of a home crowd is very real,” said Berhalter, who played for the U.S. national team and also for European and MLS club sides. “You can see how away teams come and play for a point.”

Frankie Hejduk, a U.S. World Cup teammate of Berhalter’s, echoed the sentiment.

“When you walk out of a stadium where 50,000 fans are screaming at you, where the referee is often intimidated and you still earn a tie, it’s gratifying,” said Hejduk, who played club soccer in Germany and in the MLS. “If we tied on the road, it was almost like a win for me. The effort that goes into getting that tie is almost unexplainable. It’s that way almost all over the world.”

There’s also the matter of the relegation-promotion system, a concept that’s foreign to American pro sports. When the Browns braintrust opted to tank the 2016 and 2017 seasons, they received consecutive No. 1 overall picks for finishing with a combined 1-31 record. That never happens in European soccer. The bottom feeders are banished to lower divisions and replaced with newly promoted sides.

The financial implications for relegated teams can be catastrophic. Lucrative sponsorship deals and league television money disappear. Translation: Bob Nutting isn’t buying a European soccer club anytime soon.

Earning a few precious points from draws can be the difference between staying in the top-flight league and being dispatched to lower divisions.

“A team at the bottom of the table will regard an away draw against a team near the top as a cause for celebration,” wrote Darke. “It is worth a point in the standings, and that might be the point that stops them being relegated. So the draw is very much part of the football culture and there will be no plans to banish it in any European leagues any time soon.”

Added Wickham, a Newcastle United and Browns fan: “A draw can mean a moral victory, it can change the narrative around the team, and it can be exciting. There's been some doozies in cricket, where all three results have been possible until the last ball. . . . I really don't get why (American fans get) so annoyed at a tie. It's the result that was meant to be.”

____________________

GETTY

Former MLB commissioner Bud Selig (left) huddles with 2002 All-Star Game managers Bob Brenly and Joe Torre.

Few players enjoyed their 2002 All-Star Game experience more than Williams. The former Pirates pitcher retired all three American League batters he faced in the third inning as he struck out Alfonso Soriano and Derek Jeter and induced a ground out from Ichiro Suzuki.

But as managers liberally substituted to ensure that everyone made an appearance, trouble soon appeared on the horizon. The game went to extra innings and both teams ran out of pitchers.

Where was John Nogowski to hurl a few innings when you needed him? Oh, right, he was nine-years old.

“It’s been almost 20 years, but I do think they were talking about some guys going back into the game,” Williams recalled. “I remember hearing those comments in the dugout or locker room.”

With no pitchers left, the umpires and managers consulted with Selig, who was sitting in the stands. He decided that if the game remained deadlocked after the 11th inning, it would end in a tie. The public-address announcer notified fans of the verdict and chaos erupted after the final out.

“It’s like people wanted to suit up the bat boy to pitch or something,” Wann said. “They went crazy.”

Some fans chanted “Bud sucks!” at a commissioner, who’s a Milwaukee native. Others hurled beer bottles and seat cushions onto the field.

Just days after renaming the All-Star MVP award in honor of Ted Williams, the league opted not to award it.

“I don’t remember players being really disappointed, but I know the fans were,” Williams said.

The All-Star Game tie remains one of the most memorable in sports history.

A few years later, the NHL abolished ties, allowing games to be decided by shootouts if no winner could be determined in a five-minute overtime.

“Back in the day, what may seem like a million years ago, when I was playing, we did end games in ties,” said Penguins coach Mike Sullivan. “And sometimes, as a player, those ties are satisfying because they are hard-fought ties. Inevitably, over the course of a season as long as the NHL season is, there are enough opportunities to win, and if you’re team is good enough you will end up on the right side of the score more often than not and that’s going to determine your position in the playoffs.”

However, Sullivan also sees the “practical” nature of shootouts and understands the fans’ desire for a winner and loser at night’s end.

Recent struggles aside, the shootout has been kind to the Penguins. The club’s .596 all-time winning percentage ranks second only to the Avalanche (.638).

“If you are asking me if I agree with that, is (the shootout) the best way to determine a winner and a loser, I would prefer it not to be, but I’m a traditionalist,” Sullivan said. “I value the team game. I think the fabric of the game is 5-on-5, and for me that’s the ultimate way to determine a winner and a loser. But I also understand that’s not practical through the course of an 82-game schedule.”

In some ways, it’s akin to ending an NFL regular-season game with a field-goal kicking contest. Given Chris Boswell’s accuracy, Steelers fans might want to know where they can sign up.

In the meantime, the Steelers and the rest of the league will need to find ways to end overtimes in traditional fashion. T.J. Watt helped Pittsburgh avoid an embarrassing tie with a strip sack of Geno Smith on Oct. 17 against the Seahawks.

Wann raises an interesting point, especially as it pertains to college football. Marathon overtimes are often the most memorable. He recalls sitting with his family transfixed as Texas A&M outlasted LSU, 74-72, in a 2018 seven-overtime classic.

“To this day, we still talk about that game,” Wann said. “If a game really matters, it can’t end in a tie.”

Ohio State and Michigan renew their storied rival Saturday in Ann Arbor. While the Buckeyes have dominated the series in recent years, the Wolverines had won four straight heading into the 1992 game in Columbus. That contest ended in a 13-13 deadlock and it led to one of the all-time zany quotes from then-OSU president Gordon Gee.

“This tie is one of our greatest wins ever,” Gee said.

Cam Heyward is an Ohio State alum, one who never lost to Michigan in four tries. His reaction to that remark probably would make Gee’s trademark bow tie spin like a propeller.

-- DK Pittsburgh Sports writers Dave Molinari and Dale Lolley contributed to this report.