Over the last year, I’ve had many requests to do a Mound Visit that serves as a primer for analytics and how to use them. It’s been on my “to do” list for some time, and with the lockout entering its second month, now seems like the perfect time to do it.

The question was how should I present this information. A few readers asked for a bibliography of terms, something they could presumably put in their tabs for when I cite a stat they aren’t familiar with. I thought about doing one, but there are just so many different stats that the article would be really long, really boring and not offer anything more than a textbook definition. FanGraphs and MLB.com have glossaries of many of these advanced stats, if there’s something I don’t cover and you’re interested in. (I’ll also be in the comments if that helps).

Instead, I decided to focus on five areas where teams, including the Pirates, evaluate pitchers and then showing what are some good stats to evaluate pitchers in these areas. I also included some Pirate pitchers from this last season to illustrate someone who either did well or struggled in that particular point. Hopefully, this way will introduce some next-gen stats while being able to show how someone can apply them.

Next week’s Mound Visit will focus on hitters, but we’ll start with the pitchers.

SPIN

Since the advent of Baseball Savant and Statcast in 2015, one of the most cited pitcher analytics has become spin rate. Measured in rotations per minute (RPM), it looks at

To overly simplify things, the higher the spin the better, but a “good” spin rate varies by pitch type and not every pitch needs spin to get outs. Take, for example, this Mickey Janis knuckleball, which is barely rotating:

"Spin rate? Where we're going, we don't need a spin rate." 👊 pic.twitter.com/4rX4Qd2eku

— Baltimore Orioles (@Orioles) March 9, 2021

Changeups and splitters usually have low spin rates too because the goal of the pitch is to get drop and vary speeds. There are some exceptions – like Devin Williams’ change – but spin isn’t the goal of those pitches. Sinkers and two-seamers usually have lower spin rates than four-seamers (more on that here). In these three cases, more spin could potentially be beneficial, but you’re a unicorn if you get super high spin this way.

That leaves four-seamers, sliders/cutters and curveballs as the main remaining pitches, all of which benefit from having more spin. If you want to dive into the charts, Derek Barthels of Viva El Birdos did research last month that showed that on a macro scale, more spin on a four-seamer resulted in more whiffs and worse hitter results. For breaking pitches, more spin leads to more horizontal or vertical movement.

You can increase spin a couple ways. For fastballs, the only direct way to increase spin is with more velocity. Breaking pitches can change based on velocity, grip, adjusting the spin axis and several other potential ways.

And, of course, you could add a foreign substance to a baseball. Not all substances are illegal. Rosin is provided for pitchers, and when combined with sweat alone, it can create a sticky substance. Rosin wasn’t causing the spike in spin the last two years. That was mostly driven by banned substances, like pine tar and Spider Tack. The league had a sticky stuff crackdown in June, and many pitchers’ spin rates drastically dropped as a result.

So what’s a “good” spin rate? There are varying factors, but last year, the average fours-seam spin rate was 2,273 RPM, slider was 2,416 RPM and curveball was 2,513 RPM. I usually qualify a pitch as having a high spin rate when it’s about 200 or more RPM higher than those totals.

Last year, Kyle Crick’s slider had the highest spin of any pitch in baseball, averaging nearly 3,300 RPM. We saw how that much movement could create control problems, though, so perhaps there can be too much of a good thing. Chris Stratton had the highest spin of any four-seamer on the team last year (2,610 RPM), while Bryse Wilson barely got 2,000 RPM, which can be explained by his low-90s velocity.

Baseball Savant is the best place for tracking spin rates. They have leaderboards and it’s cited on player pages. You can also chart a player’s spin rate by pitch by season, month or game, if you want to see how a player’s spin has changed over time or if they had a massive drop off after the June crackdown. Baseball Savant also tracks pitch movement, if you want to see how that spin translates to something more tangible than just a number.

Not all spin is created equal, though. There are two types of spin: "Traverse spin," which leads to movement, and "gyrospin," which does not. (See: Magnus Effect) The more traverse spin, the better. This is measured in "spin efficiency" or “active spin,” or the amount of spin that leads to movement. Active spin leaderboards can be found at Baseball Savant. The higher the better, but almost no pitches are 100%. A good fastball will be in the upper 90s and most breaking pitches are somewhere in the 70s.

There’s also spin direction, or what axis a pitch breaks towards the plate at. I wrote more about it here.

BATTED BALL DATA

Two other Statcast terms that have have become vernacular over the past few years are exit velocity and launch angle. I’ll focus on the latter more next week for hitters.

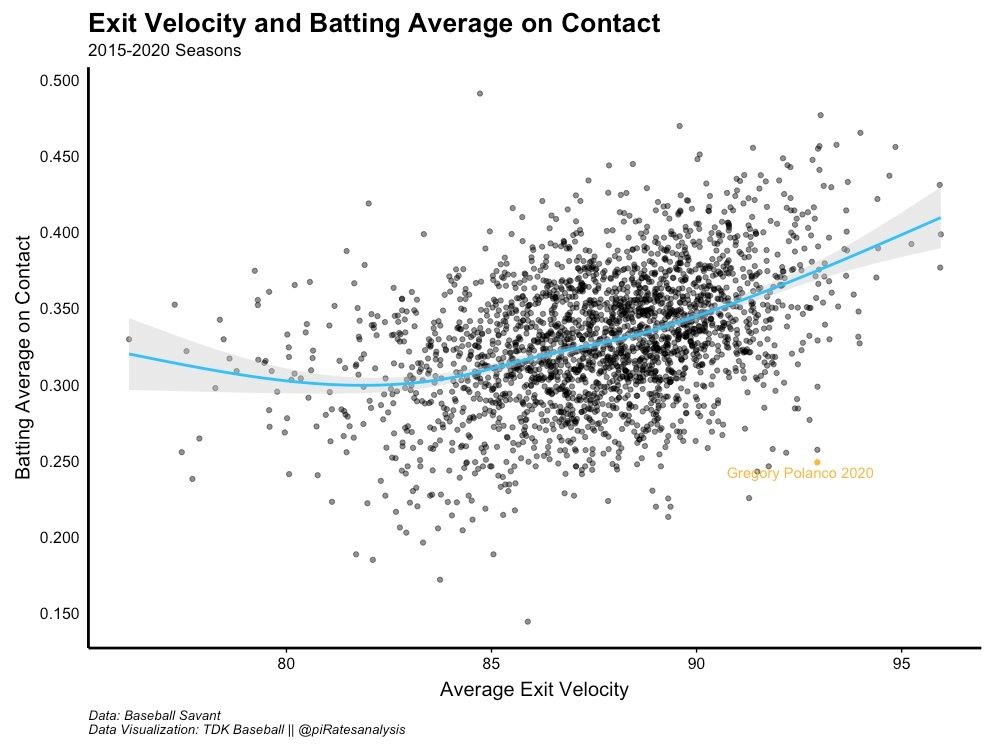

Exit velocities are pretty straight forward: At what speed did the ball come off the bat? Baseball Savant measures any batted ball that’s 95 mph or higher as hard contact. (Sports Info Solutions also tracks hard hit percentages on FanGraphs and Baseball Reference, but their criteria is different.) As expected, the higher the exit velocity, the better the results. Take, for example, this chart I published in a Mound Visit on Gregory Polanco last year:

There is a point where a really low exit velocity (swinging bunts) can result in a good batting average, but after that brief drop off, the higher the average exit velocity, the better batted ball data you have. I want to save a lot of this for the hitters next week, but it’s worth a quick mention here. Exit velocities can be found on Baseball Savant, FanGraphs and Baseball Reference.

For pitchers, some key peripherals to watch are ground ball percentage (GB%), fly ball percentage (FB%) and home run-to-fly ball ratio (HR/FB). FanGraphs have all of these in the batted ball section, and they are able to track it to the lowest levels of the minors.

These are self-explanatory. Ground ball and fly ball percentage is the rate of batted balls that stay on the ground or in the air. Home run to fly ball can offer insight for how hard hit those fly balls are, and while the league average is almost always between 10-15%, that doesn’t guarantee a pitcher’s HR/FB rate will normalize to that league average.

Cycling through some Pirate leaders last year, Clay Holmes had a 72.8% ground ball rate, the best on the team, but he paid for his fly balls with an 18.8% HR/FB ratio. Richard Rodríguez was a fly ball pitcher (57.5% FB%), but his 3.3% HR/FB kept him effective. A full leaderboard for these batted ball peripherals can be found at FanGraphs.

WHIFFS AND STRIKEOUTS

The strikeout has become a major part of the game over the past decade. Back in 2011, there were 34,488 strikeouts across the league. In 2021, that number increased by nearly one-fourth to 42,415. Even fifth starters and middle relievers need to be able to get at least some swing and miss anymore to stick in this game.

Strikeouts can be measured in a couple of ways, the easiest being just the total number. The other two best ways are strikeout percentage (K%) and strikeouts per nine innings (K/9).

K% takes the number of strikeouts and divides it by the number of batters faced.

K/9 averages out how many strikeouts a pitcher would have over nine innings. It is calculated the same way as ERA.

Of the two, I strongly prefer K% because K/9 lacks an important piece of context: How many batters did the pitcher face. If a pitcher gets hit hard and is chased after three innings, but he struck out four, then he has a 12 K/9. That’s really good and would indicate hitters were having a hard time making contact that day, when that wasn’t the case. K% would take those extra hitters the pitcher had to face into account. The difference becomes less of an issue with a larger sample size, but you can find plenty of relievers with a higher K/9 than is probably warranted. It’s a matter of choice though which one you prefer, and both are regularly cited.

Using David Bednar as an example, last year he averaged 11.4 K/9 and had a 32.5% K%. Among pitchers with at least 60 innings pitched, his K% was 15th and his K/9 was 28th, which is pretty close to each other given the size of the sample. Meanwhile, Luis Oviedo posted 9.4 K/9, a tick above the league average of 8.9 K/9, but his K% was 21.1%, a couple ticks below the league average of 23.3%. All of those walks (7.9 BB/9 and 17.7% BB%) were a big reason why. Here are some more leaders.

It’s hard to get strikeouts without whiffs, though, so keeping track of those can be just as insightful. FanGraphs gives the simplest breakdown of whiffs in their “plate discipline” subhead, tracking swinging strike percentage (SwStr%). They also offer how often a hitter made contact on a swing at a pitch in the zone (Z-Contact%) and out of the zone (O-Contact%).

In the big picture, a whiff is a whiff, so it doesn’t necessarily matter where the pitch was thrown, but it can offer some insight. Sam Howard had the lowest Z-Contact rate (74.5%) and O-Contact rate (49.4%). One area Mitch Keller has dropped off at since 2019 is how often he gets a whiff out of the zone, seeing his O-Contact rate go from 55.2% in 2019 to 67.3%, meaning that about one swing in every eight on a chase pitch is now at least a foul ball instead of a swinging strike. That’s going to extend at-bats and give him trouble.

Baseball Savant also tracks whiff rates for individual pitches, both on individual player pages and through leaderboards, but you have to go through the pain of using the search feature to find their contact rates based on pitch location. Their player pages also track strikeouts, batting averages and other stats by individual pitches.

The analysis site PitcherList kept track of a stat they called CSW%, or “called strike and whiff percentage,” valuing a called strike as just as valuable as a swing and miss. Baseball Savant and FanGraphs have since adopted the stat too.

EXPECTED STATS

So you have a pitcher who is getting good spin, encouraging batted ball data and a high strikeout rate, but their ERA is over 5.00. What gives?

Expected stats can offer a different way to assess how a pitcher has performed to that point. That doesn’t guarantee future results, in the same way a pitcher with a low ERA isn’t necessarily going to continue to prevent runs from scoring. Still, people feel more confident when the pitcher has a sub-3 ERA, when sometimes the pitcher with an ERA over 4 might have better peripherals.

The most long standing expected stat is FIP, which predicts a pitcher’s ERA based on the number of strikeouts, walks/hit batters and home runs they have on the season. There is also xFIP, which normalizes the home run rate to the league’s average. There are sometimes when xFIP can be useful – Tyler Anderson had a consistently lower xFIP when pitching with the Rockies because the ball flies out of Coors Field, which is an element he can’t control – but getting weak contact is a skill, so I prefer regular FIP.

Last year, Trevor Cahill was someone who had a much better FIP (4.06) than his actual results (6.57 ERA), something that could probably be chalked up to his small sample size and just terrible first inning results. Only the flip side, Anthony Banda had a 3.42 ERA, a nice total for a midseason waiver claim, but his 4.84 ERA painted a bleaker picture.

FIP has been around for over 20 years, though. The new wave of expected stats is on Baseball Savant, where they track exit velocities, launch angles, strikeout and walk rates to predict what a pitcher’s results should be. That includes expected batting average (xBA), slugging percentage (xSLG) and weighted on-base average (xwOBA). Using xwOBA, they are able to project it to an ERA, though it’s not quite as clean. And like spin rates, they track these expected stats on leaderboards and player pages.

I cite a lot of x-stats in Mound Visit because I believe it’s the best way to track a pitcher’s performance on individual pitches, especially since sample sizes can get small there. A couple ground ball rolling base hits could boost a batting average on a breaking pitch from .200 to .300. Of course you have to value the actual results too, but someone who is getting a lot of hard hit outs will probably not pitch as well long-term as someone who is being blooped to death right now.

VALUATION

So we have all of these new tools, many of them are researched when a team is considering acquiring a pitcher. How do we apply the results they give, besides the usual stats like ERA and WHIP?

There are individual pitch values, calculating how many runs that pitch was worth compared to an average pitcher. Baseball Savant and FanGraphs both measure it, but do it in different ways. Bednar’s fastball was graded similarly by both sources, but FanGraphs measured it as +8.6 runs above average, while Baseball Savant said it was nine runs better, or -9, than average.

The most common way, though, is WAR, or wins above replacement. What constitutes “replacement level?” The definition is it’s a player that could be had for basically free, either stashed away in Class AAA or on the waiver wire.

This is the sabermetric community’s best effort to try to quantify a player’s contributions into one number in order to compare them to other players around the league or different eras. This is done by comparing how many wins a particular player was responsible for compared to a “replacement level” player.

The two main resources for WAR are Baseball-Reference and FanGraphs, but they calculate it differently. Both have a pool of 1,000 WAR to split between the league, with 57% going to hitters and 43% going to pitchers, so with that in mind, it’s not uncommon to mix and match or alternate which version you want to use. For example, I think FanGraphs’ version of WAR is best for catchers because it takes pitch framing into account, but I prefer Baseball-Reference for pitchers.

This is because FanGraphs’ WAR is FIP based, while Baseball Reference’s is based on runs allowed. While I think FIP can be a useful tool, it’s been surpassed by many of Baseball Savant’s expected stats and doesn’t give the best look at what value a pitcher actually brings. It’s more theoretical, in my opinion.

FanGraphs’ version of WAR is commonly referred to as fWAR, while Baseball Reference’s is rWAR.

How to use it: In terms of using it, WAR is pretty simple: The higher the better. To lay out what a good WAR is, this is a good rule of thumb, with some Pirate examples, mixing both hitters and pitchers:

0 WAR: Replacement Level (Chase De Jong, -0.1 rWAR)

1 WAR: Good bullpen/bench player (Ex. Chris Stratton, 1.1 rWAR)

2 WAR: Average MLB regular (about 150 starts as a position player or 30 starts as a starter) (Ex. Tyler Anderson, 2.1 fWAR)

3-4 WAR: An impact player. Someone who noticeably contributes to make the team better. (Ex. Jacob Stallings, 3.0 rWAR)

5-7 WAR: An All-Star. An unquestionably good, or great, player. (Ex. Bryan Reynolds, 6 rWAR)

8-10 WAR: MVP candidate. (Ex. 2013 Andrew McCutchen, 8.1 fWAR)

Hopefully this has been helpful and worth the wait for those who have asked. If you have suggestions for the hitter half, please let me know.