Jon Kolb doesn’t wear any of his four Super Bowl rings, and that’s probably for the best since anyone with a real eye for diamonds might suspect forgeries. Not one to call attention to past glories, the former Steelers left tackle had many of the precious gems removed, presenting them as gifts to family members.

Some were made into earrings and a necklace for his wife, Debra. Others are found in engagement rings belonging to daughters-in-law Sarah and Katie.

“If I see a Steeler wearing a ring, he was probably watching the games from the sideline,” Kolb said jokingly.

So it should come as no surprise that the walls inside his Wexford gym, Adventures In Training With A Purpose, don’t contain any Steelers memorabilia or photos of Kolb during his playing days from the 1970s. Even his bio on the company website waits until the fifth sentence to mention his link to one of the NFL’s greatest dynasties. The rest are dedicated to his educational bona fides — his masters degree in exercise science and his past work as an instructor at three colleges.

“So many guys I think need to have a shrine to themselves,” said Kolb, 74, who still has the kind of chiseled frame that would make men half his age think twice about throwing the first punch. “You need to always be moving on, not looking over your shoulder. I’ve found in life that each venture has been more challenging and fulfilling than the last one.”

His current quest involves giving those who protect our country and serve our communities a place to exercise their bodies and unburden their minds. Kolb’s non-profit organization -- one that includes three regional training facilities -- enables active military members, veterans and first responders free access to resources that can improve their physical and mental well-being.

More than 100 people have taken advantage of ATP’s services in Wexford, Hermitage, Pa., and Youngstown, Oh., since Kolb founded the program in 2015. Military members past and present comprise roughly 50 percent of the clientele. The rest are people receiving physical therapy who no longer have the benefit of paid rehabilitation.

Kolb might not be able to give them diamonds, but his staff offers something almost as precious — an opportunity to regain movement and independence lost through accident, injury and advanced age.

Whether he’s working with a stroke victim on his balance or offering encouraging words to a Marine Corps veteran dealing with anxiety, Kolb is ever-present on the gym floor alongside ATP staff members.

“I had a regular gym membership and never used it,” said disabled veteran Kathleen Edwards, a former Air Force airman who suffered a brain injury during a 2006 convoy accident in Iraq. “I have trust issues and panic attacks and I don’t like to be out in the public very much. But going there and working with the staff has helped me get out of my comfort zone.”

At a time in life when many seniors do nothing more strenuous than play bocce or lob underhand tosses to bat-wielding grandkids, Kolb remains in full flight. He moves with the purpose of a man preparing for another training camp.

Look at this video in which he demonstrates the core-shredding “Windshield Wiper:”

That was shot 10 years ago, but Kolb is still performing the exercise.

“It’s windshield wipers rain or shine,” said Kolb, who finished fourth in the 1978 and 1979 World Strongest Man competitions.

It pays to stay fit when you are constantly on the go, trying to raise funds and solicit public donations. Practically the entire Kolb clan works for the ATP cause. They are constantly pursuing grant money so military members and first responders can keep rebuilding their bodies and nourishing their souls for free.

“I don’t know how you compress all the things that impress me about Jon into a couple of sentences,” said Steelers radio analyst Craig Wolfley, a longtime friend and former teammate. “He’s a real cowboy, not a hat-and-buckle wannabe. A granite chin and a soft heart. A man who went into a flaming farmhouse to save his (2-year-old son Eric.) A gentle teammate who carried my father, in the last stages of dying from cancer, into my wedding and stood by his side throughout the ceremony and most of the day.”

____________________

STEELERS

Jon Kolb played for the Steelers from 1969-81.

Kolb tells stories the way great pitchers throw curveballs. They start outside the strike zone before breaking across the plate and buckling your knees.

His affinity for the military has obvious roots. Kolb served in the Army National Guard for about five years after becoming the Steelers’ third-round pick in 1969. There’s also his well-known connection with teammate Rocky Bleier, who became a four-time Super Bowl champion after recovering from multiple leg wounds in the Vietnam War.

Tuesday, Kolb sat in his office and told another military-related tale that began with child’s play at an Oklahoma grade school.

“Gary Southern was my best friend from back in the days when we shot marbles together— I don’t think kids today do that anymore,” Kolb said. “He also scored the last touchdown of our high school football careers. We beat Oklahoma Military Academy 65-0. I don’t remember a Super Bowl score, but I remember 65-0.”

Without warning, the rotation in Kolb’s meandering story starts to break.

“I got a scholarship to Oklahoma State,’’ Kolb said. “And Gary got a scholarship to Vietnam.”

The two chums loved to take long boat rides together, but after the war Southern rarely spoke in Kolb’s presence. Something had changed and, Kolb not understanding the reason for his friend’s reticence, didn’t appreciate the silence. The men drifted apart.

In 2009, Kolb was elected to the Oklahoma Sports Hall of Fame, where he donated his Super Bowl rings for a display. Out of nowhere, he received a call from Southern, who volunteered to pick him up at the airport. As they were walking from the terminal to the car, Kolb glanced at the bottom of Southern’s license plate.

“BRONZE STAR,” it read.

Kolb felt like he has been hit with a Lyle Alzado head slap.

“I’m sitting in the car and I’m thinking to myself: ‘How upside down is this? I’m getting a banquet for running into people on a football field,’” Kolb recalled. “As we’re riding from the airport, like an idiot, I say, ‘You got the Bronze Star. What happened?’ I thought Gary was going to break the steering wheel. He said softly, ‘There was an ambush and a lot of guys didn’t come home.’ That’s all I got.

“I ripped up my speech for the induction ceremony and threw it away. I just talked about Gary.”

TOM REED / DKPS

Marine Corps veteran Gary Ciccone works out at the Wexford facility.

The physical damage a soldier or a first responder suffers in the line of duty is often evident to the general public. But what of the emotional and psychological scars?

“What we see is a lot of people who have unseen wounds they’re working through like post-traumatic stress, anxiety and depression,” said Kolb’s daughter-in-law Sarah, ATP’s director of development and marketing.

It’s why the program offers members more than a room full of weights, treadmills and rowing machines. ATP partners with Fortis Future to provide psychotherapy and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). It’s an intense 12-week course in which clients meet individually with a clinical psychologist and receive daily TMS treatments.

Chad Weaver, 39, said the course and his workouts in the gym help him cope with anxiety and depression. He’s experienced both in his time as a state trooper and a soldier fighting in Iraq.

“Mentally, it helps me,” said Weaver, an infantry rifleman who was part of the 3rd Battalion, 25th Marines Kilo Company. “It’s almost like an awakening. I come here five days a week and I leave with a better attitude. It recalibrates things in my head.”

Gary Ciccone, 38, a former infantry squad leader in 2nd Battalion, 6th Marines Echo Company, said just coming to the gym and mingling with others has been therapeutic. He misses the camaraderie he enjoyed on tours through Iraq, Afghanistan and Okinawa Island.

Kolb is deeply troubled by the suicide rates among veterans. He sees at least one common thread between former football players and military personnel.

“What is your mission now,” he asked rhetorically. “These men and women are so used to having a mission, and when they get out, what’s left? Part of my theory is that we should help them figure out what their next mission in life is going to be.”

____________________

STEELERS

Jon Kolb acknowledges fans at Heinz Field in 2021.

Weaver said Kolb never talks about his football career unless someone asks him to tell stories about his days playing for Chuck Noll and protecting Terry Bradshaw’s blindside.

There’s at least one tale that could put a smile on anyone’s face in the gym, a story that sounds as though it was ripped from the pages of “North Dallas Forty.”

“You’ve heard the expression, ‘All hat, no cowboy,’” Kolb said. “That was Terry.”

The Hall-of-Fame quarterback portrays himself as a good ol’ boy from Louisiana. He’s recorded country songs and appeared in Burt Reynolds’ movies. But Kolb, who grew up in a small Oklahoma town with “no traffic lights and five Baptist churches,” has seen Bradshaw’s greener side of country living.

Kolb invited Bradshaw and fellow offensive lineman Gerry Mullins to his old farm in Greene County. The first sign of trouble was Bradshaw’s inability to properly saddle a roping horse, Kolb said. Things only got worse.

Bradshaw wanted to see Kolb rope a calf while on horseback. With no other animals in the pasture, the quarterback volunteered to start scrambling the way he did when flushed from the pocket. This was Bradshaw’s second mistake.

“He’s running and saying, ‘You can’t catch me,’” Kolb recalled. “I got near him and roped him. Now, I got to get the rope off of him. The horse is trained to back up. Terry keeps walking up to her. I get off the horse and I’m walking to Terry and all of a sudden he says, ‘What happens if she spooks?’ Well, that spooked her and off they go.”

The horse dragged Bradshaw twice around the pasture like a tin can on a string that's attached to car with a “Just Married” sign on the bumper. Kolb and Mullins already were wondering how they were going to break the news to Noll.

“There was dew on the grass and all I could see was this spray, and they are going through the pasture and Terry is bouncing up and down,” Kolb said. “I knew he was alive because he was yelling ‘help, help!’”

Kolb eventually grabbed the reins, but not before the horse dragged him as well.

“To show you how much linemen love each other,” Kolb said, “Mullins hops off the fence, steps over Terry and says, ‘Kolbie, are you all right?’”

Bumps and bruises aside, everyone involved played in the next game.

Decades later, it makes for a great story, one that can lighten the mood of anyone having a bad day in the gym.

____________________

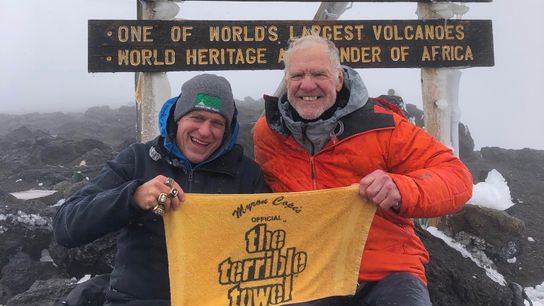

SARAH KOLB

Jon Kolb, right, with Kevin Cherilla, of Pittsburgh, at the top of Mount Kilimanjaro.

Kolb’s days of mayhem ended in 1981 following his retirement from the Steelers. He’s still, however, spoiling for one final fight. Not with a man or a team, but an entire profession.

He grows animated discussing insurance actuaries, whose duties include determining when their company should no longer cover physical-therapy sessions for a policy holder. It’s an unenviable task involving mathematics and risk assessment, and it makes Kolb angrier than the sight of former division rivals.

“I’d loved to be put in a Greek coliseum with all the actuarial science people and give them the weapons,” Kolb said. “Insurance companies hire these guys. Most of them come from Cleveland, I think.”

Kolb worked with hospitals and rehab centers after leaving his Steelers’ post as a strength-and-conditioning coach in 1992. Watching patients lose their insurance coverage for treatment spurred him to branch out on his own and launch the ATP program.

He opened the Youngstown and Hermitage sites seven years ago. The Wexford facility followed in 2020.

“The United States is a great place to have a heart attack,” Kolb said. “We’ll fix you up as good as new. But if you have a chronic condition, meaning long term — Parkinson’s (Disease), a stroke, multiple sclerosis, ALS . . .those are things that happen as we get older. The United States is not such a great place to be dealing with them.”

ATP’s support of veterans and active military members was recognized by the NFL last year. Kolb was voted the Steelers’ nominee for the Salute to Service Award.

For someone who doesn’t like individual attention, Kolb received plenty of it in 2021. He also was among four former Steelers inducted into their Hall of Honor, along with Carnell Lake, Louis Lipps and Tunch Ilkin. It proved to be a bittersweet weekend due to the Sept. 4 death of Ilkin following his one-year battle with ALS.

Kolb and Ilkin shared many passions, including a strong Christian faith and a desire to help vulnerable members of the Pittsburgh community. During the last year of his life, some of Ilkin’s best days were spent in Wexford at ATP, attempting to build his stamina on a portable underwater treadmill that he dubbed “my happy tank.” Ilkin was still logging his nautical miles 10 days before his death.

Wolfley will never forget the kindness and commitment Kolb exhibited in working with Ilkin at the gym.

“He’s a man of God,” Wolfley said. “Love, compassion, courage, admiration, brotherhood and mentor are words that come to mind when you mention his name.”

Kolb conquered the NFL and even scaled Mount Kilimanjaro with family members several years ago. While his Super Bowl rings may be filled with cubic zirconia, few doubt the authenticity of the rugged Steelers lineman who won them.

“There are people who spend their whole life worried if a glass is half-full or half-empty,” Kolb said. “The purpose of the glass is to drink from it, refill it and drink from it again.”