Mario Lemieux's the greatest hockey player who ever lived.

He's also the most ... prolific?

Take this, please, from someone who covered Mario's career, who considers having done so to be the greatest honor of my own career, and who forever has advocated for that first sentence up there: I still couldn't ever be convinced that he was more outright prolific than Wayne Gretzky until, oh, yesterday.

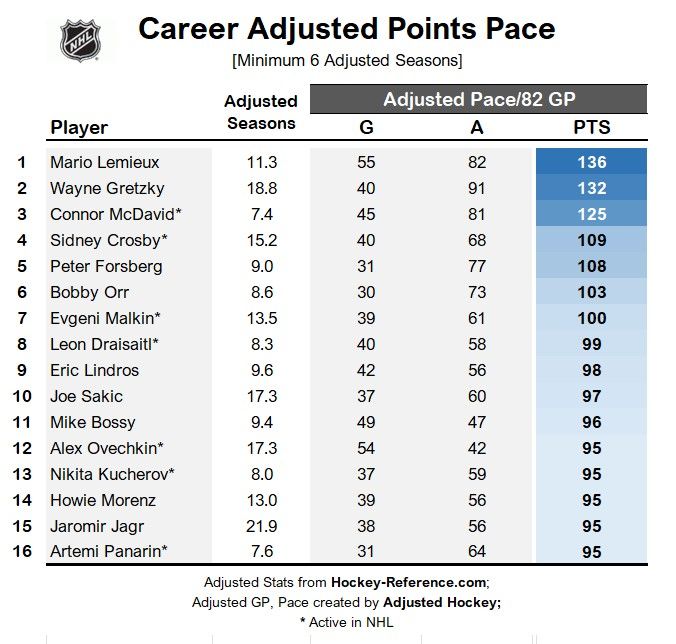

Check this out:

It's just insane even at a glance, right?

And you'd better believe I'll get to Evgeni Malkin's placement, as well, down below.

But first, an explainer: Paul Pidutti, a hockey statistician based in Sudbury, Ontario, researched and released the above chart for the website Adjusted Hockey earlier this month, aimed at evening out all era-related criteria and coming up with, plain and simple, who'd produce the most points over an average season regardless of when it occurred.

And Mario's simply the best, to paraphrase the Tina Turner tune that often serenaded him on Civic Arena ice, with an average of 136 era-adjusted points over an 82-game span. By comparison, Gretzky averaged 132, followed by two active players in Connor McDavid at 125 and Sidney Crosby at 109, then Mr. Postage Stamp himself Peter Forsberg at 108.

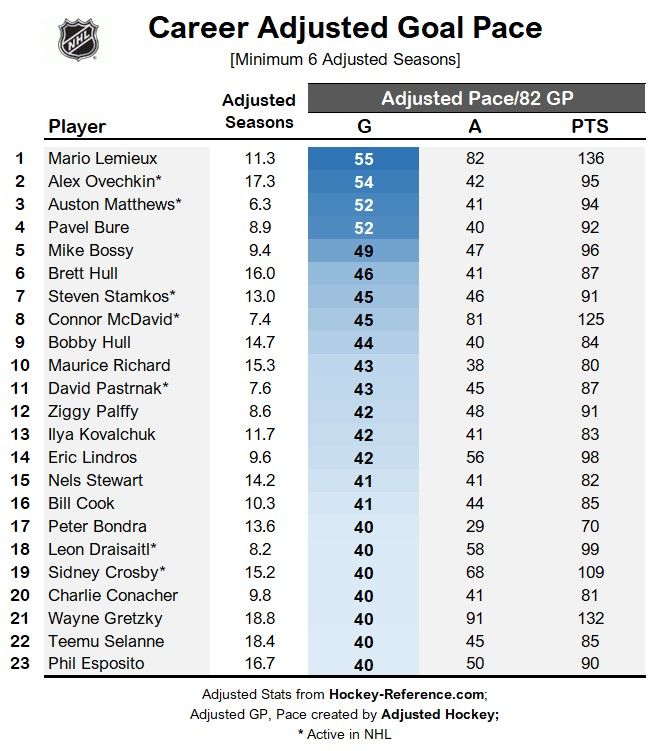

But wait, there's more:

Oh, my! No. 1 in goals, too!

In fact, Mario and McDavid are the only two players to make both top-10 lists but with the mindblowing caveat that Mario's on bleeping top of both!

Pidutti's formula isn't fancy and, really, it's little different than those that illustrate in other sports -- notably baseball, which has the longest lineage in the United States -- how to put Honus Wagner and Babe Ruth into the same contexts as Roberto Clemente or Shohei Ohtani: It takes the general level of points and goals scored in a certain era, applies that as the framework in which the player operates, then adjusts the figure to reflect the performances fairly.

For example, Mario's career straddled both the go-go 1980s of the NHL, in which goaltending equipment was as scant as the defensive scheme in front of them, and the mid-1990s mastering of the neutral-zone trap by Jacques Lemaire's Devils, in which it was almost possible to see New Jersey's scheme behind Martin Brodeur's refrigerator-sized pads. So in Mario's case, he'd have been hit with a reduction for, say, his 199-point masterpiece in 1988-89, while also a boost for the winters when he had to battle through hooking, holding and backtracking defensemen.

Now, is this definitive?

Heck no. I don't even see it as all-the-way fair, especially to Gretzky. Because if there's any one column that stands out between Nos. 66 and 99 in those charts up there, it's the chasm in the number of seasons, Mario's 11.3 to Gretzky's 18.8. There are real rewards historically for longevity, and no truly great athlete should ever pay a price for hanging around for nearly two decades. Mario had his well-known illnesses, other issues and, of course, the intermission retirement. We can all speculate how many more points he'd have put up if he never stopped after this phenomenal moment, which, believe it or not, was the first Penguins game I covered for the Post-Gazette:

I swear, I can still feel the place shaking.

We could also, just for fun, speculate how many more Stanley Cups he'd have raised.

But what we can't do, I feel, is to punish Gretzky for being fortunate enough to be able to push through without interruption and, thus, being forced to include the 62-point for-him-dud in his final season, 1998-99 with the Rangers at age 38.

Right?

OK, well, on the other hand -- if only because one can go back and forth on this debate for all eternity -- Mario famously emerged from retirement at age 36 and, in one of the most impressive feats in any professional sport anywhere on the planet, climbed back to the pinnacle of his craft in, oh, as I recall, 33 seconds or so:

In the 91 games he'd play over that season and the next, he'd pile up 122 points, including 34 goals.

At the ages of 36 and 37.

And I'm not even touching on the comeback from cancer, the back ailment that kept him from being able to lace up his own skates in the 1991 Stanley Cup Final or a billion other exotic storylines along the path.

So allow me to steer this in a different direction. Mario did things on the ice Gretzky couldn't dream of doing. And not just the goal-scoring, as Gretzky once nobly acknowledged himself. Mario was the better shooter, the better skater, the bigger body, the greater force (when applied) defensively, and even in the areas where most experts grant the checkmark to Gretzky -- his vision and passing -- the truth, as I see it, was always a draw with both.

I could keep blathering, or I could just present this ...

... and posit that Gretzky, respectfully, couldn't do those things.

Not that it'll change the narrative any more than Pidutti's elegant study. Gretzky will forever be royalty in Canada, which will, as long as I live, hold exclusive rights to all hockey narratives. And to speak this bluntly, Mario's French-Canadian background would never have allowed him ... not just to ascend to Gretzky's level but even to challenge it anywhere up north but in Montréal itself.

But that's fine. I'll take it. I'll embrace it, actually.

I'll also embrace, as promised, that Malkin pops into that points pack at an eye-popping seventh place in averaging 100 points. Behind Mario, Gretzky, McDavid, Crosby, Forsberg, Bobby Orr ... there's Geno. Mr. 101 himself, as some will ruefully recall, all the way up at No. 7. And he's there after a high total of 13-plus era-adjusted seasons, including this past one in which he logged all 82 games and put up 83 points at age 36.

Never forget that. Be sure Geno doesn't.

Anyway, era-adjusting's an inexact science, to say the least. Ruth's almost universally seen as the greatest era-adjusted player in any major North American sport, based on his home run total as compared to his peers of the era. But in the same breath, it can be spoken that Ruth's peers never really began even swinging for the fences until he'd became a living legend for it. Out-of-the-park home runs just weren't a thing in baseball for its first half-century. So some might argue, as I have, that Ruth's achievement is better compared to that of Orr, whose arrival utterly flipped hockey onto its face in that he was the first defenseman to do what he did.

Even there, though, I'll conclude with a card to play on Mario's behalf: He did everything better than everyone else. He didn't pioneer too much, other than this woefully under-appreciated no-touch 'assist' on Paul Kariya's Olympic gold-medal clinching goal at the 2002 Salt Lake City Games:

But he didn't need to. He played whatever game anyone played and just played it better. He did that in the '80s, the '90s, then out of retirement into this century. And he still did it better than anyone.

What's to adjust?

I'll leave you guys with this NBC video from six years ago, when my friend Mike Emrick asked Mario, Gretzky and Orr if they could still be great in the modern NHL: