It was April 1, 1987, and Andy Van Slyke and Mike LaValliere are stuck on the Sunshine Skyway Bridge trying to get to Bradenton, Fla.

The duo had just been traded from the Cardinals to the Pirates for Tony Peña, the Pirates' All-Star, Gold Glove-winning catcher. We know now that the two would go on to become cornerstones of the team's three division winning teams in a few years.

Assuming, of course, they could get to Pirates spring training. There had been an accident on the two-lane bridge early that morning, and with no way to turn around or phones to call ahead, they had no choice but to sit through the bumper-to-bumper traffic.

"I remember thinking we're going to go in there, make the best impression, get there at 7:30 in the morning, and then there was the accident and we pulled in like a couple of pompous a------- at 11:30," LaValliere said.

As the hours ticked by and their chance at a good first impression long gone, Van Slyke asked LaValliere a question that neither one of them could answer.

Who was the manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates?

“Really, it was a bad day for me, going from the Cardinals – first place, World Series – to the Pirates, who finished last three years in a row," Van Slyke said. "So why would I know the manager?”

When the two players eventually did make it to Bradenton and walked into the manager's office, they were introduced to the team's second-year skipper, Jim Leyland. In that first meeting, Leyland asked LaValliere, who had worn No. 10 with the Phillies and Cardinals, if he wanted that number with the Pirates. LaValliere quickly realized that was Leyland's number and declined, even after Leyland tried to nudge him to take it.

"I'm thinking, is this a test, or is this guy really that much of a good guy," LaValliere thought.

Decades later and that's still not clear. Those two and the hundreds of others who could pass through Leyland's teams through his 22-year managerial career would go on to find out that this mustachioed son of a Perrysburg, Ohio factory worker could rip profanitiy-filled postgame tongue lashings as well as he could Menthol heaters, and demanded respect for his players, coaches and himself. They would also learn that underneath that exterior was one of the smartest baseball men of his generation, an expert motivator and someone who genuinely cared about people.

As the two left the office, Leyland had one more question for Van Slyke.

"Did you even know who the manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates was?"

____________________

Decades later, any Pirate fan worth their weight in batting gloves knows who Jim Leyland is.

His 1,769 managerial wins ranks 18th all-time. He managed a World Series champion in 1997 with the Marlins, two more pennant winners with the Tigers in 2006 and 2012 and the World Baseball Classic for team USA in 2017. But he is perhaps best known for his 11 years managing the Pirates, where he led a successful rebuild in the direct aftermath of the drug trials and the looming threat of relocation to three division titles.

“As a Pittsburgher, I thought he was as big a name as [Barry] Bonds and Van Slyke," John Wehner said. "This guy, who nobody had ever heard of when they hired him, became one of the faces of the franchise. He was one of the architects to turn things around.”

36 years after the trade that made him a Pirate and that meeting in Bradenton, Van Slyke recognizes Leyland as "the most underrated manager in baseball history." He may have finally shed that distinction, though.

On Sunday, Leyland was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame via the Contemporary Era Committee. He has the credentials for the game's greatest honor, and while players like Bonds and Van Slyke may have gone on to win more awards, one would be hard-pressed to find many managers with more stories than Leyland.

Pirates bench coach Don Kelly played for Leyland on the Tigers for four years from 2009-2012. And while he's a coach for the local ball club and a Mt. Lebanon native, Kelly knows why he gets invitations to speak at charity events now.

"I just have to tell Jim Leyland stories," Kelly joked.

Ahead of this Hall of Fame vote, DK Pittsburgh Sports reached out to long-time Leyland players and coaches to try to compile those stories -- or at least the ones that were decent enough to print -- to find out what makes one of the greatest managers of this modern era of baseball.

“I can tell some funny stuff and some unbelievable stuff, but the bottom line is he’s the best baseball man on earth as far as knowing the game, handling people, the whole ball of wax," Leyland's long-time assistant coach and friend Rich Donnelly said. "I wish we were all 20 years younger, because he’d manage for 20 more years.”

____________________

Rich Donnelly, assistant coach: “I was at college in Xavier. The guy across the hall was a guy called Smokey Knorek. He had a band that played at all the functions, so we talked a lot and I liked him. He said to me, ‘if you ever get to pro ball, I’ve got a buddy in Perrysburg. His name is Jim Leyland. If you ever see him, you tell him Smokey said hello.’ So that year, I’m playing with the Orlando Twins in the Florida State League. We are playing the Lakeland Tigers. I look at the program and Leyland is catching for the Lakeland Tigers. So I said, when I go to home plate, I’m going to say hello to him. So I walks up, I tap the plate, I look at him, and say, ‘Jim, Smokey Knorek says to say hello.’ He says, ‘that’s f---ing great, now get in the box and hit!’ ”

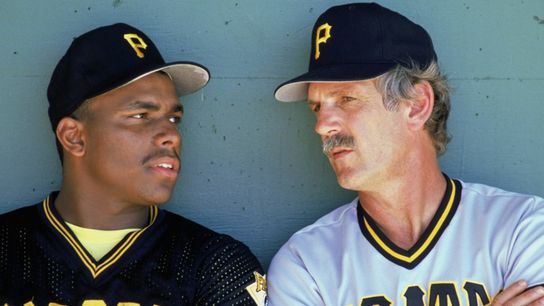

GETTY

Jim Leyland talks with Bobby Bonilla in the dugout.

____________________

In 1980, Leyland was managing the Evansville Triplets in the Tigers' organization when his team was taking on the Oklahoma City Phillies. The Triplets had a blue-chip prospect at the time, but the Phillies hit him a couple of times. Eventually, Leyland had enough. He flew out of the dugout and started going crazy. First he went to the umpires to do something. He wasn't satisfied with the results, so he ran out in front of the opposing dugout.

The dugout was actually dug into the ground, so there wasn't a fence guarding the players, and the warning track in front of the dugout was gravel. Leyland started screaming at the opposing team, pointing at them and eventually kicking gravel. The umpires grabbed onto him, trying to pull him away.

The Phillies were shocked with what they were seeing.

"We're all sitting there on the bench, watching this crazy guy kick all this gravel on us because he's trying to protect one of his players," Bob Walk said. "That was my very first meeting, seeing of Jim Leyland. And a few years later, he's my manager."

It was a fitting introduction to the Leyland the baseball world would get to know, but Leyland's public persona was one side of him. There was also the man. The guy who would cry with players when the time called for it. The guy who moonwalked to celebrate winning a division title with the Tigers. The guy who is called "Hump" by all his friends after Gene Lamont gave him the nickname because of his singing, reminiscent of Engelbert Humperdinck. Leyland can more than carry a tune, too. Donnelly remembers Leyland getting called up to sing with the Pittsburgh band The Vogues once and being the best singer on the stage.

“He’s very much a softie," Jay Bell said. "I’ve seen him weep, singing a song or honoring an anniversary or birthday. He’s very thoughtful and kind."

He just can have different ways of showing it to connect with his players. Like in Houston, for example, he would drill golf balls off out of his 23rd-floor suite. Van Slyke couldn't believe it, so he went to the room to see if it was true. It was, and Leyland asked if he wanted to go out into the pitch black of night to shag the golf balls. Van Slyke loved the idea.

“If you asked your All-Star center fielder to go catch golf balls in the dark, you’d be fired the next day," Van Slyke joked. We couldn’t see them coming down. It was like grenades being thrown in the dark... We were like golden retrievers out there. That’s all we were.”

____________________

John Wehner, utilityman: “A week before [my major-league debut], there was an emergency landing. Leyland had some heart problems, so they were flying to Cincy and had to stop in Columbus to get his heart checked. That was a week before I get called up. So I’m mulling around the clubhouse, I go to the lunch room. Here comes Leyland in his underwear with no shirt on in the lunch room. Looks up and says, ‘Wehner? S---, I knew you were coming and I almost had a heart attack.’ And then he walked out.”

____________________

"He can live with bad results," Bell said, explaining his manager's mindset. "He did for many years and on a lot of different teams. Nonetheless, he had an expectation for his players, and that was to prepare well. If you prepared well, he can live with whatever the outcome is.”

There are few that prepared like Leyland. Donnelly roomed for years with the manager and would be woken up by the smell of Menthols and countless lineups written out, planning out which matchups he was looking for and what his players would do in those spots.

In-game, he would try to keep managers on their toes. Shea Stadium's bullpens were incredibly large, so he once warmed up a third pitcher in the bullpen, having him throw sideways to the mounds to Donnelly. The hope was Mets manager Davey Johnson wouldn't know who was coming in to pitch. It worked.

In early days, he and Donnelly would go over the minor-league stats looking for players. Before the first year, they went over Walk and Leyland asked if he ever had a losing season in the minors. He hadn't.

"That's what I want," Leyland said. "A winner."

“He knew what he had and he knew what he was trying to do to try to rebuild it," Doug Drabek said. "He was good at getting the most out of a player that he could, especially the young guys.”

“He lived and died with every at-bat, every pitch," LaValliere said. "He cared about the team, and we all knew that, and that’s a special feeling."

For young guys like Bell, Wehner and Kelly, a lot of that nurturing came with open door conversations. Leyland didn't back away from questions from his players about decisions he made in games. There's no need to fear when he properly scouted and vetted out the scenarios. It could be a tool to teach. Bell would often be the first person at the stadium to just sit and talk with his manager. Perhaps he saw a future coach in the making. More than likely, that didn't matter.

“It was a regular thing for me to go into his office before the players got there to talk about the game and talk about life," Bell said. "He was accommodating to all of us. He wanted to get the best out of his players, and there was a lot of ways to do it.”

____________________

Doug Drabek, right-handed pitcher: “I remember one spring training I pitched, I didn’t throw well at all. Nothing went right. It was horrible. He came out to get the ball from me, and he was probably just a few feet away from me and I gently tossed it about six inches in the air to him. Ran off the field, got my stuff, ran into the locker room. It was just one of those bad days. As soon as I got into the locker room and threw my stuff in my locker, I turn around and he was right there, nose to nose, and he aired me out good. I pleaded my case. No disrespect. It was horrible. I was p---ed off. I didn’t want any part of it anymore. He said, ‘I understand that, but don’t ever disrespect me or another manager or another coach again!’ Then the next day, during BP, shagging BP, he comes out to me with his hands crossed. He looked me and goes, ‘I really got in your ass yesterday, didn’t I?’ I just started laughing.”

____________________

The 1993 season was not particularly kind to the Pirates. The team's three straight division titles were now in the rear-view mirror and many of the veteran players from that group had left in free agency or been traded away. That did create some playing opportunity for young players like Kevin Young, though. The team still had some veterans around, like Dave Clark, to help Young navigate the big leagues, and some postgames.

One night the Pirates blew a lead amid an ugly stretch. After the game, Young was about to hit the showers, when Clark stopped him.

"Don't even think about going into the shower yet," Clark told the rookie.

“I didn’t know what we were waiting for," Young said. "Sure enough, you hear this profanity-laced tirade from his office. You hear the crescendo coming, and sure enough, he’s in the locker room area, and he’s just letting it rip.”

A Leyland postgame tirade is part masterclass of the profanities of the English language, part stand-up routine and always completely justified.

"He was so good at yelling, you'd almost enjoy getting yelled at by him," Walk said.

"Every other word is a profanity," Young said. "You've got to piece it together. It takes a little bit."

To rattle off some of the more memorable one-liners:

• “You’re not a pimple on a big-leaguer’s a--.”

• "I keep hearing you talk about a roll. A roll is a f---ing thing you put butter on."

• "Gentlemen, it's a quarter to four. By four o'clock, I want everyboy to be out of here because there are two police offices that will come in here and arrest you for being big-league ball players."

• To bench player Gary Varsho: "Varsh, hurry up and get on the back of the plane before the GM knows you're on the team!"

There was nothing static about it, both in vernacular and movement.

"He likes to walk, doesn't like to look at anybody, and he just screams and yells through the locker room, through the shower," LaValliere said.

And the other trademark, as players like Young would find out, is they were rarely one and done. Often times there would be a pause, and then he would come back out for another round or tell of telling.

“You never knew when they were over," Walk said. "He’d go back into his office, but then he would think of something and then start all over. First timers on the team wouldn’t know that.”

"He had to go reload on the Marlboro," Kelly explained.

“When you were younger, he scared the crap out of you with his rants," Wehner said. "They would go on for a while. They weren’t five minute rants. He’d go out, scream at ya, tell you how horse s--- you were. He’d go away, come back a minute later.”

One of the most memorable for those early 90s Pirates teams was the team had lost a couple games in a row in Montreal and their lead in the division was shrinking. The chow line postgame was silent until someone said, "we'll get them tomorrow."

Leyland raised his plate over his head and smashed it while screaming, "get them tomorrow my f---ing a--!" Pieces of porcelain went flying into the salad bar and spaghetti, ruining the dishes. It was cathartic, and the Pirates righted the ship shortly after en route to the playoffs.

“Every time he lost his mind, he was 100% right," Kelly said. "100% right. And as you got to know him and play for him, he cared about his players, he cared about his staff, he cared about the people around him and he cared about winning.”

Those rants went with him to Miami, Colorado and Detroit. Those who were with him long enough got to be in on the joke after a while too. After a lengthy speech in 1998, Leyland passed Wehner and jokingly asked, "that was a pretty good one, wasn't it?"

One time when working the room, Leyland kicked a coffee table that was full of spit cups. One landed on LaValliere's head and he had tobacco spit going down the side of his face.

“I just put my head down and I just started laughing," LaValliere said. "I couldn’t help it. He finishes his tirade and the next day he comes to me and says, ‘you can’t be laughing when I'm doing that. I had to f---ing quit because I was going to start laughing too.’ ”

But that was what made him a master psychologist, in Donnelly's eyes. He could recall another game against the Reds where the team had played hard but just fallen short. The players expected Leyland to be in rare form that night. Instead, he had a quick address for the team: "If I had to go to war, I'd go to war with you guys." Again, it was what the group needed to hear.

“Besides being the smartest baseball men on earth, he is one of the best handlers of people," Donnelly said. "He could read people. He could read teams.”

“It’s a foot in the butt when it needs to be, and it’s the genuine tears down his face of joy when you succeed," Young said.

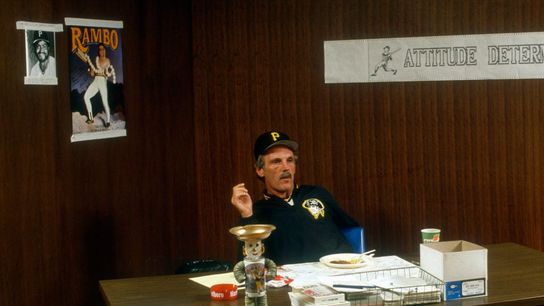

GETTY

Jim Leyland sits in his office.

____________________

John Wehner: “I was terrible in spring training. In 11 years, I made only three teams out of spring training… [In ’95,] he told me, ‘Rock, you want to make this club? You know what you need to do?’ What? ‘You need to go f---ing fishing, because I’m not going to f---ing use you. If the f---ing GM sees you, you’ve got no f---ing chance of making this club. So go f---ing fishing. Come back at the end of camp and I’ll tell you if you made the f---ing team. You’ve got no f---ing chance if that GM sees you. If you see the GM, walk the other f---ing way.’ … I went 0-for-8 and made three errors and I didn’t make the team.”

____________________

The most legendary of those tirades unquestionably happened in spring training 1991.

There was a team rule that photographers and journalists must stay in foul ground during practices and stretches. Bonds had a personal photographer that year, and they began taking photos while standing in fair territory. Bench coach Bill Virdon told Bonds that the photographer wasn't allowed to be there, and Bonds pushed back.

"If you disrespect Bill Virdon, watch out," Donnelly said.

What happened next was the stuff of yinzer legend:

The video was picked up on ESPN and replayed periodically. After the work day was done, Donnelly and Leyland went back home and put on ESPN. Leyland laid on the couch, dragging on a Menthol when the video came on.

"You want him?" Leyland asked Donnelly.

"No, get rid of him, he's a troublemaker," Donnelly responded.

Some time passed and ESPN played the video.

"You want him?" Leyland asked again.

"No, get rid of him," Donnelly said again. "I don't want him. He disrespected Bill. He disrespected you. We'll be better off without him."

More time passed and the video played again. Donnelly stood up to get a drink.

This time, Donnelly asked, "you want him?"

"You're damn right I want him," Leyland answered.

While that may have been the most memorable moment of their player-manager relationship, many of the people interviewed, unprompted, brought up how they got along and worked well together. That went for other high profile players too, like Gary Sheffield and Miguel Cabrera.

“Those guys loved him because of the way he went about his business," Wehner said. "He stayed out of your hair, but he expected you to go out there and play the game right and play the game hard, and that’s what they did.”

____________________

Mike LaValliere, catcher: “I remember one spring. I was always fighting the weight problem. It wasn’t a problem for me, but evidently for the front office, it was. I came into spring training and I was really light for me. I had lost 25-30 pounds. Halfway through spring training I hadn’t got a hit yet. He calls me in his office and says, ‘you know you haven’t made the team yet.’ And I go I’m trying. He says, ‘you look better in the uniform, but you don’t run any faster. You’re not any quicker. You can’t hit worth s---. So I want you to go out tonight and eat as many cheeseburgers and drink as many beers as you can.’ I say, ‘I’m trying to do this thing with the weight.’ He says, ‘I’ll take care of the front office. You just put on some weight so you can f---ing play again.’ That night I probably gained 11 pounds and the next day I had three or four hits. I gave a little wink and we were all good.”

____________________

Bell can't quite remember how he felt after his first two demotions to the minors. Was he sad the first time and mad the second, or was it the other way around?

But in 1989, after his third trip back down to the minors, he was definitely down, and wondered if he was going to stick. It was just his first year with the Pirates, and things were not going well until Leyland talked to him before a game against the Mets.

"He walked up to me prior to batting practice and told me, ‘Jay, they’ll have another manager in Pittsburgh before they have another shortstop,’ " Bell said. "And at that point, I felt the weight of the world off my shoulders. I felt like I could come to the ballpark and play.”

Leyland was right, too. He would leave for the Marlins a few weeks before Bell was traded in the winter of 1996.

Knowing where everybody stood was important for Leyland. In 1991, he asked Varsho, a backup outfielder who hailed from Wisconsin, if he had any "cheeseheads" coming down to watch him play when the Pirates took on the Cubs at Wrigley Field. Varsho said yes, and Leyland told him those friends would see him playing in the outfield. Varsho homered twice and drove in six runs to propel the Pirates to victory. After the game, Leyland asked if those same cheeseheads were going to be around the next day. Varsho said yes.

“You tell them that if they want to see you, they can see you in the lobby, because you’re not playing again until September," Leyland said.

“But that’s the genius," Donnelly explained. "Guys know their place. I don’t give a s--- if he got 12 hits. Bonds is playing tomorrow.”

Donnelly also recalled another time with Wehner in spring training. At the end of camp, Wehner was called into the manager's office, usually bad news for someone on the bubble. With his head down, Leyland delivered his decision.

“Godd----- Rock, you can’t f---ing hit, you can’t f---ing field. You can’t throw, you’ve got no f---ing power.

"But you’re on my team.”

Everything Leyland needed to say came through in that. Wehner had made the team, but barely. He was going to have to do the little things to stay with the team. For him, that ranged anywhere from pinch-hitting because Leyland knew Curt Schilling was going to retaliate by throwing at the hitter and he couldn't risk a star getting hurt, to pinch-running, being a defensive replacement, whatever.

“That’s great baseball wisdom: Knowing what you have, knowing what you expect and letting the players know what you expect," Van Slyke said.

Walk figured that out first hand. He was the last player Leyland said was on his opening day roster his first year. The 24th man.

"Then he looked at me and said, ‘make sure you get off to a good start, because I’m looking for a left-hander,’ ” Walk recalled.

"That’s him," Walk continued. "He’s not trying to be mean. He just wanted to make sure where I stood. That’s the way he always was, to everybody.”

“One thing that really stuck with me is all a manager really wants to know is that they can trust you," Young said about the biggest lesson he took from Leyland. "That really resonated with me, and I share it with young players.”

Of course, that trust can be twisted for some fun. Towards the end of his career, Leyland called Walk into his office. It was the trade deadline and the Pirates were rebuilding again, so he told his starter that he had been traded. The two hugged and cried. After a few minutes, Walk asked who he had been traded to.

"Do you really think someone would f---ing want you?," Leyland responded. It was all a hoax.

A few years later during spring training, Walk had begun his career as a broadcaster. Leyland called Walk into his office and confessed that he was short on arms.

“Serious as a heart attack, he asks, ‘how long would it take you to pitch an inning?’ ” Walk said.

Walk brushed it off, thinking Leyland was pulling his leg again. He wasn't going to bite. Leyland said he wasn't joking. He just needed someone he could trust for a couple months, and he could fix it with the front office and the Pirates' broadcast team that Walk could resume his broadcast duties without interference. Walk finally started to buy into what Leyland was saying and said he could be ready in a couple weeks.

“He gave me that look and said, ‘who the hell do you think you could get out?’ " Walk said. "He had me again.”

____________________

Bob Walk, right-handed pitcher: “After a clinching game, it was the year John Hallahan passed away. Hoolie was our clubhouse guy going all the way back into the 50s. He passed away during the season. We won the division that year. Hoolie and I had become pretty close, and I walked back to the old batting cage we had at Three Rivers during the big party. I went back there because I was thinking about Hoolie and I was a little sad to myself. I’m sitting in there having my beer, champagne, whatever it is we’re having. I hadn’t been in there 60 seconds. I just wanted to get away, be by myself for a moment just to think about Hoolie, maybe have a drink to have. Then Leyland walks in, just him. He goes, ‘what’s up? Why are you in here by yourself?’ And so I told him, and we start talking about Hoolie and both our eyes start tearing up a little bit. He goes, ‘Hoolie would want us to go in there and enjoy everybody.’ He certainly would.”

____________________

Part of Donnelly's duties in his Pirates years was organizing spring training, one of the more difficult tasks for any coach. All it takes is a hiccup to alter plans for the day, so meticulous care must be taken.

Leyland understood that, so he told Donnelly, "it don't have to be perfect, but it better be."

That, in a contradiction, is Leyland.

“He wasn’t expecting perfection, but he was expecting you to give whatever you had and give that out there," Drabek said.